This past New Year’s Eve, there was no shortage of conflict between revelers and police along Bayou St. John. I personally witnessed a city garbage truck chow down on a wooden barge that was to be set into the bayou near Magnolia Bridge and lit on fire—an extension, perhaps, of the

debates over New Year’s Eve bonfires in Mid-City over the past decade.

The bayou, you may not be surprised to learn, has been the site of many “fringe rituals” over the centuries—as well as plenty of city-sanctioned recreational activities too, of course. New Orleans seems to specialize in these kinds of tensions; apparently we simply cannot resist the opportunity for a bit of fun, no matter the potential repercussions.…

In perusing the City Engineer’s Bridge Records from 1918-1967 this past summer, I found a letter from Walter Parker, Chairman of the Bayou St. John Improvement Association and future New Orleans mayor, to Honorable George Reyer, Superintendent of Police, dated April 10, 1934:

“It would help a great deal were some of your men to pass along the Bayou as frequently as practicable. Some boys who do not have bathing suits, do not hesitate to bathe in very scant underwear. At the Dumaine Street bridge many boys make the dangerous practice of climbing on the bridge structure. At the Magnolia Bridge (Harding Drive) boys dive from the top of the bridge pretty much all day. In so far as I know, people have a right to fish on the Bayou. But when they leave crab bait, old papers and remnants of lunch behind, they create a nuisance. I have found that such things usually are the result of thoughtlessness rather than viciousness, and a simple request or word of warning brings a correction….” [1]

Many of you have probably heard about the annual St. John’s Eve voodoo ceremony that takes place on the Magnolia Bridge every June 23rd. Bayou historian Edna Freiberg explains that after the Haitian Revolution, New Orleans authorities began to get jittery about potential slave uprisings in their own city. On October 15, 1817, City Council forbid people of color from congregating in large groups “except in times and places specified by authorities.” [2]

Following this mandate, voodoo rituals moved to the untamed upper bayou, along the shores of Lake Pontchartrain, where the authorities wouldn’t be as likely to quash them. The voodoo rituals performed on the bayou today may be an extension of these religious ceremonies pushed to the fringe by the powers that be. (More on this when I conduct in-depth research on the subject.)

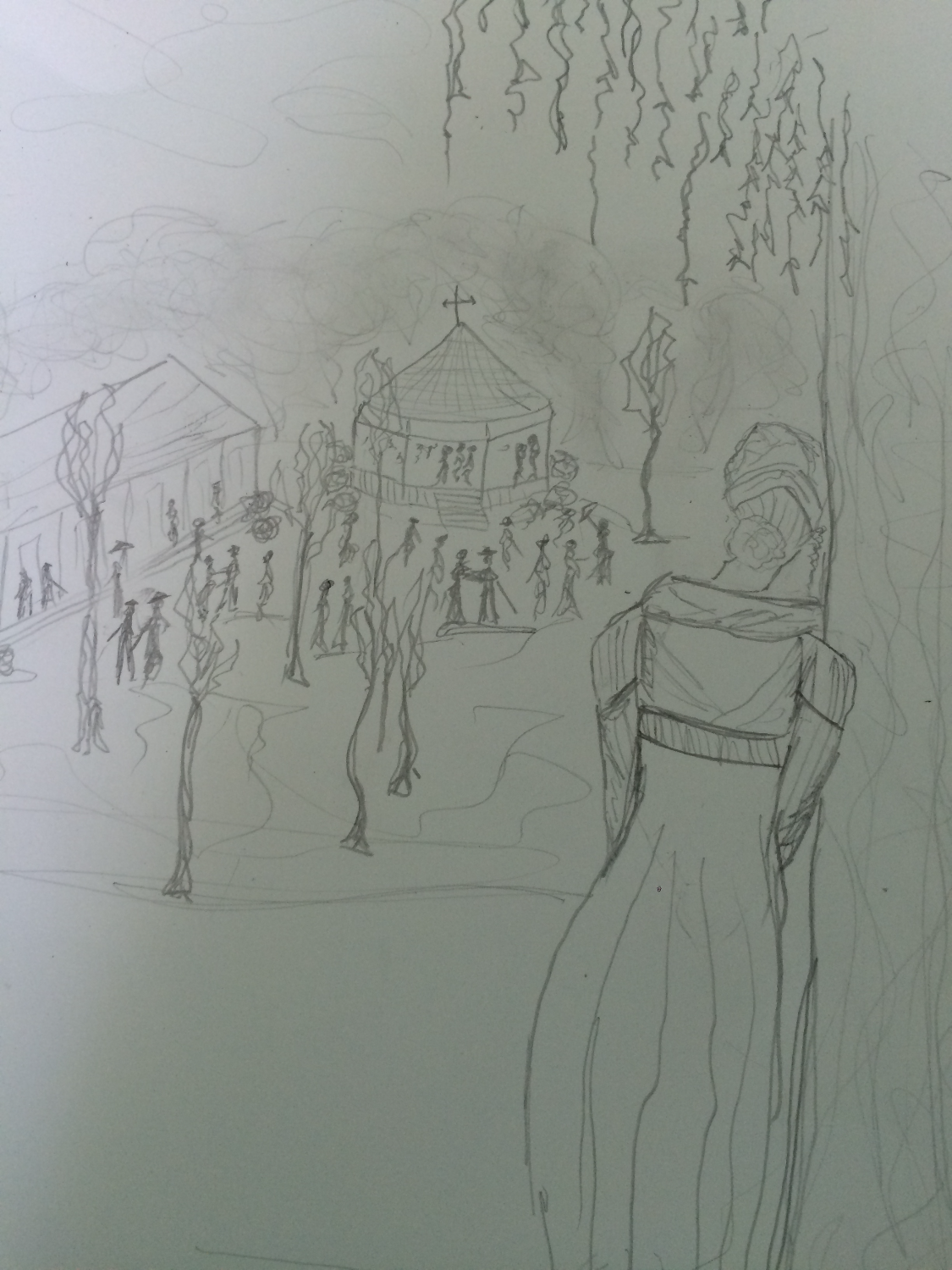

Aside from the recreational pursuits of the New Orleans elite in the 19th and early 20th centuries (rowing races for which thousands of finely-dressed spectators turned out during the summer months; picnics at Magnolia Gardens, where visitors could purchase beer and ice cream; sketching parties on the bayou’s banks; a “young ladies rowing club,” complete with “costumes” and “chaperones”; and “pleasure drives” along the shell road to Lake Pontchartrain, to name a few), neither was there a shortage of ad hoc recreational events along the bayou during those years, some deemed more acceptable than others.

Readers may remember a “strange duel” I mentioned in a previous post, for example.

Or take this Times-Picayune piece from June 20, 1872, in which a set of “loafing rowdies” are up to no good: “The attention of the police is called to the fact there is a crowd of men who daily congregate on or about the bridge over Bayou St. John and demean themselves most disgracefully. They appear to find especial pleasure in making use of the vilest sort of language, yelling, singing unchaste songs, and insulting persons whose necessities carry them in that direction. This sort of thing has grown to be an intolerable nuisance, and should be abated at once. Bayou St. John is one of our most popular afternoon promenades during the heated term, and the ladies and gentlemen who seek recreation and pleasure at that point are entitled to a share of police protection from the misconduct of loafing rowdies. It is suggested that one or more officers be stationed near the bridge, day and night, as the services of the police are very often needed by the residents in the neighborhood.”[3]

And one of my favorite examples, from 1876: “A goose race is proposed to come off at Bayou St. John next Sunday. There will be several contestants, each in his tub, which will be drawn upon the water by six geese. There distance will be one hundred yards.”[4] Does anyone else feel like a hundred yards is actually pretty far to travel via goose-drawn tub?

Or an example of the kind of entertainment one might hope to find on a summer’s day at Spanish Fort: “Prof. Clark, the renowned swimmer, appears again this evening and to-morrow in a series of difficult feats on water at the lake end of Bayou St. John. This novel exhibition is to include eating, drinking, and writing under water; also a military drill by the skillful Professor. To the end of providing for the many going, the cars of the City Park and Lake Railroad will run every half hour without fail.”[5]

Lastly, although this is a bit of a stretch, I wanted to include the strange recreational habits of a Mrs. Taylor Shatford, who lived for a time on Bayou St. John: “It was in 1916, after a trip abroad, that Mrs. Shatford became convinced that she was controlled by the spirit of Shakespeare. Operating with a ouija board she began to take dictation from him, and later declared she had trained her psychic senses…and could actually hear the words from his ghostly lips.”

The article provides us with a snippet of The Bard’s genius-beyond-the-grave, via Shatford’s ouija board: “‘We carry here the man we were. Our longings, like, some hatreds as of yore. And I who wove my rhyme am he, the same, except for my soul’s tears. To all who yearn to know if still man lives without his bones I say Complete. He dies never. His ashes are remnants of his suit. I have my whiskers still.”[6]

See?! Even the long-dead William Shakespeare can’t resist shenanigans the bayou every now and again!

1. New Orleans City Engineer’s Bridge Records, 1918-1967, City Archives Louisiana Division, New Orleans Public Library

2. Freiberg, Edna B., Bayou St. John in Colonial Louisiana 1699-1803. (New Orleans: Harvey Press, 1980) 294.

3. “The City. Public Hacks and Hack Drivers. Their Condition And Future Prospects.” Times-Picayune 20 Jun. 1872: 2. NewsBank. Web. 13 Jan. 2016.

4. “City Gossip.” Times-Picayune 29 May 1876: 2. NewsBank. Web. 13 Jan. 2016.

5. “Aquatics At Spanish Fort.” Times-Picayune 14 Jul. 1876: 1. NewsBank. Web. 13 Jan. 2016.

6. “Spirit Of Shakespeare Works Through Medium Revelations of Poet Made in New Orleans to “Medium.” Times-Picayune 11 Jan. 1920, |: 33. NewsBank. Web. 13 Jan. 2016.