In learning recently of a 2013 archaeological dig at the colloquially termed “Spanish Fort” site on Bayou St. John, my fascination with this spot was renewed. The dig, conducted by FEMA, revealed a Native American shell midden peppered with fragments of animal bones, pottery, clay pipes, and other artifacts dating from the late Marksville period, from around 1,600-1,700 years ago.

Instead of destroying it entirely, as early colonial accounts had suggested they’d done, the French simply sliced off the top of the midden and used it as a foundation for the wooden fort they built there in 1701. The Spanish then reinforced the fort in the latter half of the 18th century, and the Americans reinforced it still further in 1808.

Although the fort never saw much military action, the piece of land it sits on has seen an astounding amount of human activity over the past 2,000 years. Throughout much of the 19th century, the site was a popular spot for picnics and swimming, boasting a resort hotel catering to New Orleans elite looking to escape the city and spend an afternoon on the shores of Lake Pontchartrain.

After a fire destroyed the hotel in 1906, the New Orleans Railway and Light Company built an amusement park that drew New Orleanians to the site by the thousands. By the 1920s, activity at that crook of land between Bayou St. John and the lake began to decline when the Orleans Levee Board began their extensive Lakefront Project, “reclaiming” land from the lake in Orleans Parish and fortifying it with a sea wall.

That’s a lot of activity for one small slip of bayou bank! The site has “worn many hats,” you might say—first a shell midden hat, then three different kinds of fort hats, then a hotel hat, then an amusement park hat…. What a stylish and versatile hunk of mud! Such elaborate head-pieces!

What follows are some quotations and photographic snippets of these many layers of Spanish Fort history.

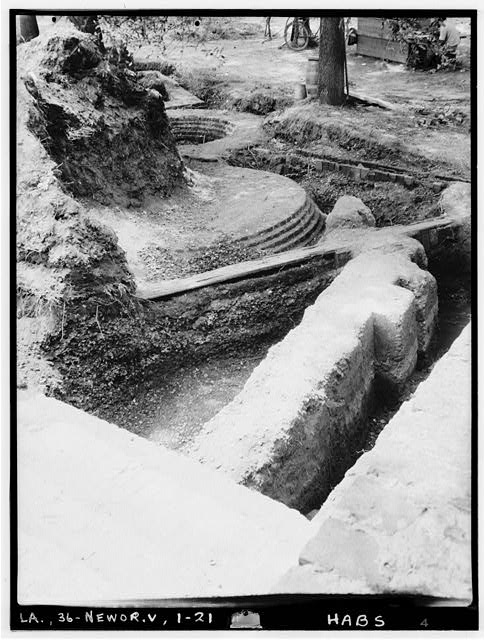

From the Library of Congress, a 1934 photo taken as part of the Historic American Buildings Survey. Look at all those layers of fort!

A notice posted by Louis Lacuna & Co. in the July 4, 1841 Times-Picayune:

The fine Hotel at the Lake end of the Bayou St. John is now ready for the reception of visitors, having every variety for amusement—Billiards, pistol shooting, bathing, &c. The Restaurant is furnished with the best the markets afford.”[1]

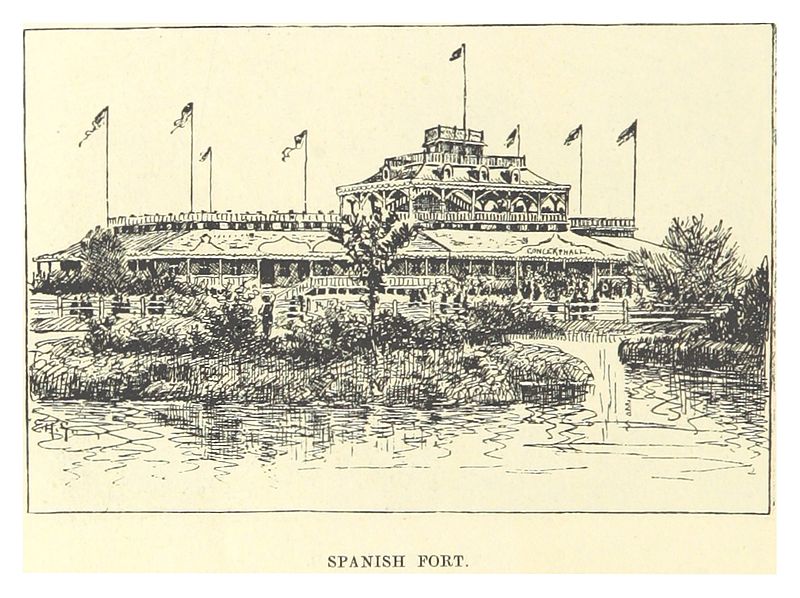

From Wikimedia Commons, a circa 1883 drawing of the Spanish Fort by Mark Twain (!) from his book Life on the Mississippi.

From a book written by Eliza Ripley, called Social Life in Old New Orleans, published in 1912, we have a description of the “Lake End” resort and what its fine dinners can do for a person’s femininity:

“There was a large hotel (there may be still—it is sixty years since I saw it), mostly consisting of spacious verandas, up and down and all around, at the lake end of the shell road, where parties could have a fish dinner and enjoy the salt breezes….The old shell road was a long drive, Bayou St. John on one side, swamps on the other, green with rushes and palmetto, clothed with the gay flowers of the swamp flag. The road terminated at Lake Pontchartrain, and there the restful piazza and a well-served dinner refreshed the inner woman.”[2]

(In reading this, I can’t help but wonder if that shell road was paved with shells dredged from the midden at the Spanish Fort site….)

On December 30, 1913, the Times-Picayune ran a full-page ad for New Orleans Railway and Light Co., in which the new amusement park was mentioned:

“SPANISH FORT: A historical spot situated on the lake shore at the junction of Bayou St. John. A delightful resort, operated in summer with music, vaudeville and light opera. Full of romantic reminiscence,—a beautiful spot, shaded with an abundance of trees and other shelters. In the summer there are many attractions, various amusement devices, restaurants, casinos, and ice cream parlors. An excellent electric train service from Canal and South Rampart St.”[3]

Some Spanish Fort diners in a Library of Congress photo titled “Afternoon scene of Reno’s Restaurant,” dated May 27, 1912. I love being able to see the movement of passersby just off the patio to the right….

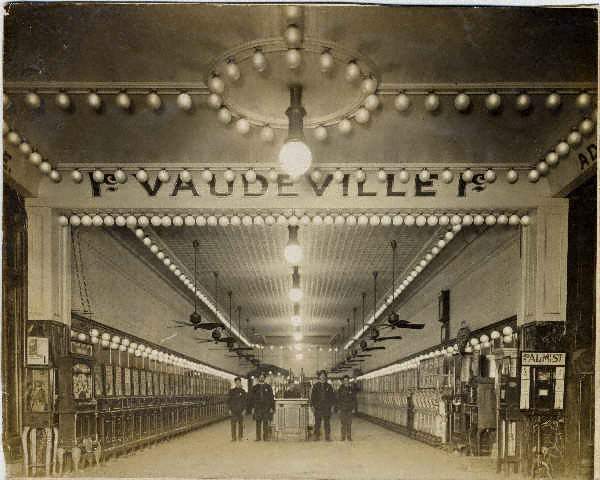

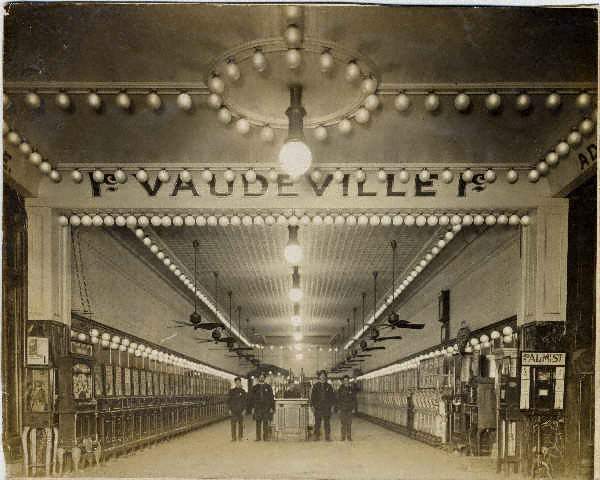

From Wikimedia Commons: “‘Fitchenberg’s Penny Arcade’ at Spanish Fort amusement park, New Orleans, circa 1910,” photo by John Norris Teunisson.

Lastly, a rollicking description of the Spanish Fort amusement park in its later years from the Times-Picayune, June 8, 1924:

“NEW RECORD MADE AT SPANISH FORT—Popular Lake Resort Reports Heaviest Attendance in Its History—The last week witnesses a new record for crowds at Spanish Fort amusement park. Despite the rain thousands of Orleanians attended the dances at Tokio Gardens and made a round of the various amusements and concessions, including the Giant Dipper, the Dodgem, the Whip, the Caterpillar, the Merry-Go-Round, the Penny-Arcade and other attractions. As usual Emile Tosso and his concert band drew a heavy patronage….Tokio Gardens continues to be the center of attraction of the younger dancing set of the city, and any night until midnight hundreds of dancers attend. Of all the thrilling attractions at the park, the Giant Dipper seems to have the most appeal. The thriller is a mile long and is negotiated at the rapid speed of 57 seconds. Second in popularity is the Dodgem, which has all the excitement of a railroad wreck with none of the dangers. The Whip, next in choice of the crowds, is the famous ride first established at Coney Island. The Caterpillar is especially popular with young couples. It consists of riding under cover in the dark at a rapid speed in an artificial cyclone.…With the increase in temperatures many persons are finding relaxation at Tranchina’s bathing pavilion where all facilities for an enjoyable swim are at hand, including dressing rooms, towels, lockers, bathing suits and other equipment, such as slides and chutes of the finest type.…”[4]

Shooting through the darkness with one’s sweetheart “at a rapid speed”—that Caterpillar sounds positively scandalous!

From Wikimedia Commons, before the Lakefront Project extended the lake shore: “Aerial photograph of Spanish Fort Amusement Park, New Orleans, 1922. Showing intersection of Bayou St. John and Lake Pontchartrain, “camp” houses on piers in the shallows of the lake, and undeveloped (pasture) land to the south.”

There are many mysteries associated with the Spanish Fort that I didn’t get into today—like the unmarked grave enclosed by an iron fence at the site, or the unidentified Civil War submarine that was hoisted from the bottom of the bayou next to the fort over a century ago, now housed in the Louisiana State Museum in Baton Rouge, or the strange rock sculptures that may be associated with the amusement park of yesteryear still visible to those driving by….

If this doesn’t inspire you to visit the quiet, unassuming Spanish Fort ruins of today—in order to imagine the waves of activity the site has witnessed over the years—then I don’t know what will!

1. Times-Picayune 4 Jul. 1841: 3. NewsBank. Web. 16 Dec. 2015.

2. Ripley, Eliza Moore Chinn McHatten,Social Life in Old New Orleans, Being Recollections of My Girlhood.(New York; London: D. Appleton and Company, 1912) 63.

3. Times-Picayune 30 Dec. 1913: 24. NewsBank. Web. 16 Dec. 2015.

4. Times-Picayune 8 Jun. 1924: 67. NewsBank. Web. 16 Dec. 2015.