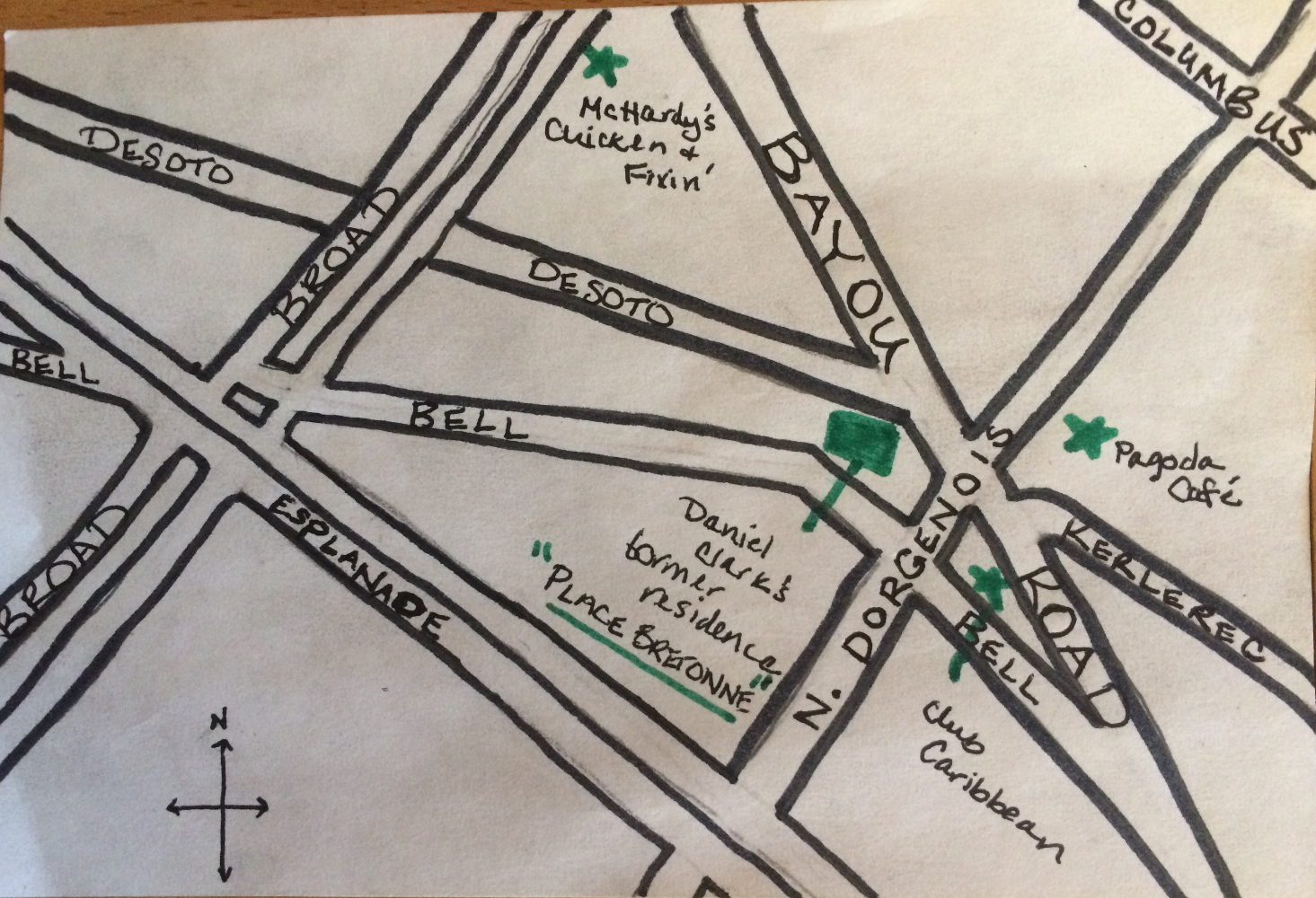

“Water hyacinths blocking a steam boat on a bayou in Louisiana in 1920.” October 25, 1920, photo from Louisiana Works Progress Administration collection. Note: the bayou in the photo is not Bayou St. John.

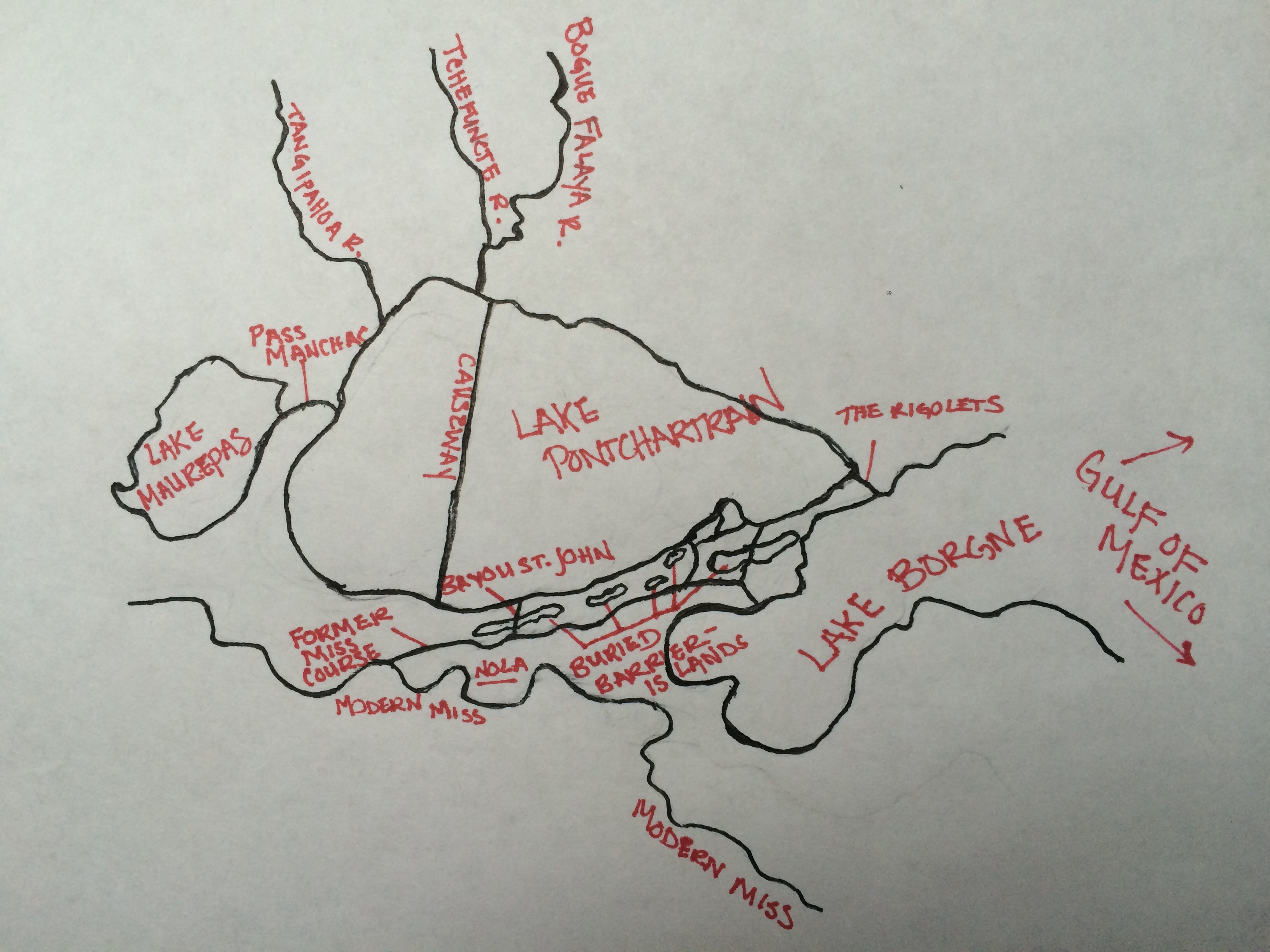

In writing a recent post on fish in the bayou, I learned a bit about the decision to intermittently reopen, back in 2014, the lock separating the waters of Bayou St. John from those of Lake Pontchartrain. But apparently this most recent debate on a stagnant and unhealthy bayou was not the first of its kind—not at all!

I still have some research to do on the construction of the lock at Robert E. Lee, decisions surrounding bayou health over the course of the 20th century, etc. But until I have all the answers, here are some interesting tidbits on our troublesome friend:

In 1952, a Times-Picayune headline claimed: “Bayou St John Acting Up Again: Surface Scum Permeating Area with Bad Odor.” A caption beneath a photo of the weed-choked bayou read: “Malodorous Stuff Blankets Water Near City Park Entrance.” I’ve decided we don’t use the word “malodorous” enough anymore…. let’s resurrect it (just in time for Mardi Gras)!

The article goes on to explain: “Members of the Bayou St. John Improvement Association reported Friday that scum forming on the surface of the bayou has permeated the area with a gagging smell….” Public Buildings and Parks Commissioner Victor H. Schiro noted that this phenomenon was certainly not isolated (“‘We have [this] trouble every year…’”) nor was it a small problem: “‘All week we’ve had a crew of six to eight men collecting the scum off the water. They’ve moved six truckloads of the stuff all ready. We’ll probably be doing this for another month.’” Wow. That’s a lot of scum.

Schiro said he didn’t quite understand the phenomenon, but attributed it to vegetation growing on the bed of the bayou that, during certain times of year, rose to the surface. “‘It’s like a flower that comes to bloom,’” he said.

The article wraps up with a final thought from Schiro: “‘There’s not much we can do about this except to try to keep the bayou clean….Whenever we say anything about closing the bayou the people raise the devil, so we do the best we can under the circumstances.’” All around the city, open canals were being buried and covered over, including the bayou’s younger sister, the New Basin Canal. Therefore, filling in the bayou to avoid this kind of nuisance wasn’t a fanciful idea. Nonetheless, the bayou was clearly as beloved then as it is now, despite its smelly antics. [1]

One more fun fact: in 1953, they were back at it, trying to get rid of the problematic vegetation. A Times-Picayune headline read: “Bayou Clearing Work is Started, But Undergrowth’s Weight Brings Halt for Repair.” I will quickly summarize the gist of the article: a war surplus amphibious “duck,” a 2.5-ton, six-wheel “truck and barge combined, equipped with a propeller and capable of locomotion on land and water,” outfitted with a special metal basket at the end of a boom, was being used to clear the bayou of its organic mess. However, this amphibious behemoth was no match for the bayou’s impressive undergrowth. The weight of it broke the boom, and the “duck” had to be sent back to the Sewerage & Water Board for repairs. The bayou was said to have tweeted: #sorrynotsorry #iamwhoiam[2]