In 1907, then Mayor Martin Behrman made a formal offer on behalf of the city for “four small islands” in Bayou St. John. When I first came across this story in the Times-Picayune I was flabbergasted. What islands?! I had never heard them mentioned before. And also, what does an “island” in a slack body of water, often only a few feet deep in places, look like? To me, growing up in Maine, an island is a large hunk of rock rising out of the ocean, or maybe a medium-sized hunk of rock rising out of a lake. They are stable, with lots of vegetation. Often they have piers. Often they have cemeteries. If not a pier and a cemetery, then at least a rope swing. Often there are blueberries.

I digress!

But it all comes down to my having misconceptions about a) islands, and b) the bayou.

See, I knew that Park Island (sometimes called Demourelles Island), located at roughly the midpoint between the lake and the foot of the bayou, isn’t really an island. Well, I mean, it’s an island in the sense that it’s a mass of earth surrounded by water, but let’s just say it wasn’t formed naturally and that mass of land didn’t always identify as an island.

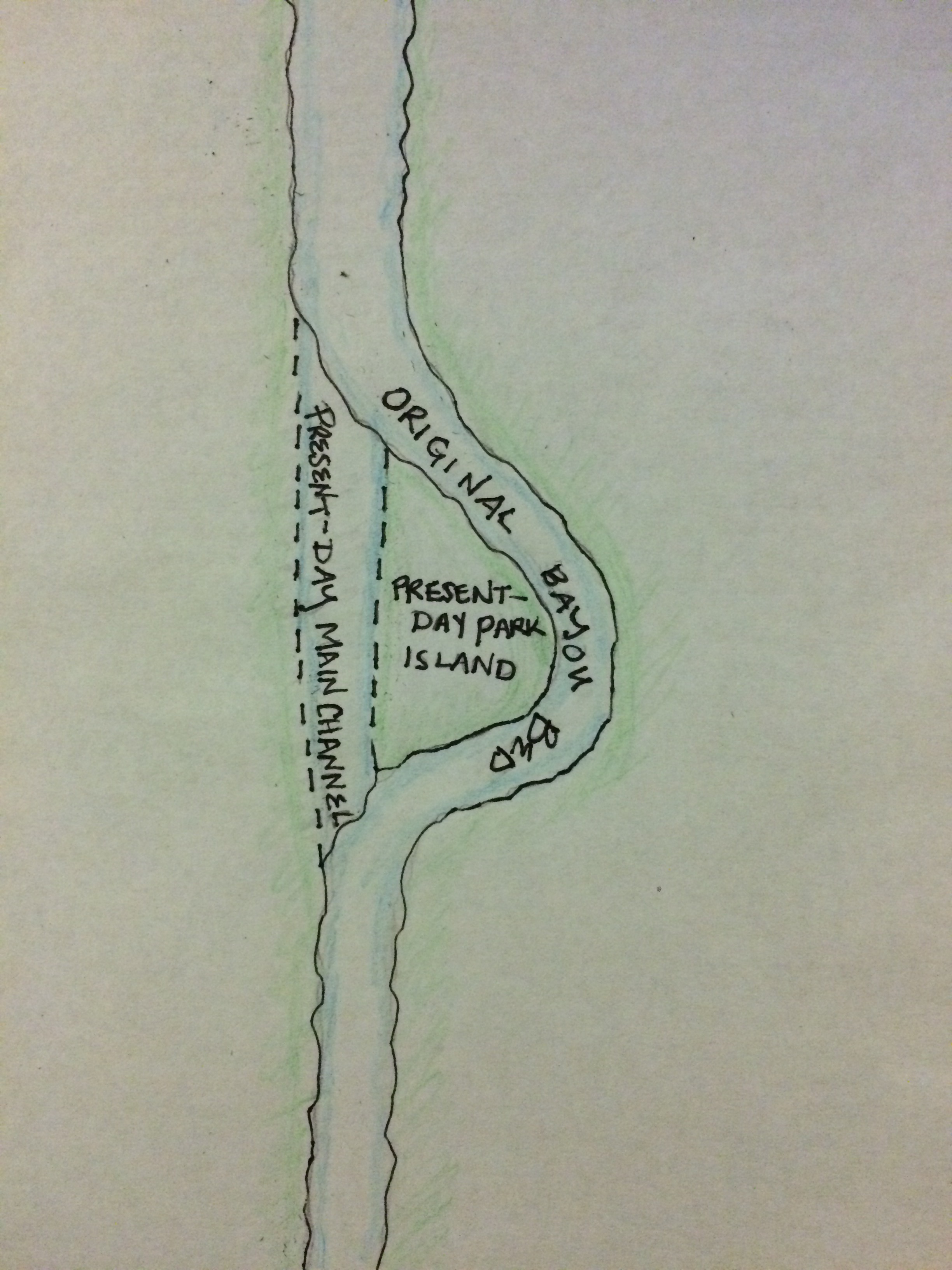

Fun fact: in the mid-1800s, in order to avoid a sharp curve that was often clogged and impassable, they straightened the bayou. The bayou’s original bed forms the eastern channel that flows around today’s Park Island. The island itself is made up of the original bed’s western bank and the earth they dredged to make the new channel.

Which is all to say, I thought I knew something about the bayou and its island (singular).

Which is all to say, I thought I knew something about the bayou and its island (singular).

But I didn’t!

When Behrman made his first offer on the islands, a couple years prior to his second offer in 1907, it was denied by the Register of the Land Office because the islands “had no official status” and were “therefore not subject to sale.” A clue in the subsequent sentence makes it clear why: “…1906, a bill passed by the General Assembly providing for the sale of lands formed by receding waters, whether navigable or unnavigable, became a law….” So these islands, in having no official status, had to have been recently revealed by the bayou’s waters, which were, for whatever reason, becoming shallower. [1]

A friend and fellow researcher in the neighborhood has uncovered some tidbits in his travels regarding these “four small islands,” which, when added up, were said to have encompassed 6.38 acres—an area roughly equivalent to the 200-foot-wide strip of the bayou’s western bank between Orleans and the bayou’s foot (where Bayou Boogaloo sets up every year). A document detailing ownership of this piece of land references a 1906 survey (which cannot be located) in which the bayou was described as splitting into an eastern and western channel in that location. Between these channels is where the four islands were said to reside. [2]

I haven’t been able to find these islands in any early maps, but nonetheless the maps make clear that the bayou once forked and split and spread its fingers in all kinds of directions as it approached what is now the heart of the city.

So, in other words, I was completely wrong to have assumed the bayou couldn’t have “real” islands of its own. This New Englander stands corrected.

<

<