Dear Readers,

In exactly one week, I will be turning over my manuscript on the history of Bayou St. John to the publisher. You might be able to imagine the brain-fry that’s happening over here in order to make this deadline. The marathon stints of revising and citing and formatting have left me a little….blank. As in, I’m dreaming about the bayou—about writing about the bayou, in particular—but when it comes to crafting a short, interesting piece on some bayou anecdote: I’m coming up a little dry (no pun intended!).

Then I remembered a post I’d started and abandoned a few months ago. It quoted a Times-Picayune article featuring some of the most flowery language I’d ever heard in my life (appropriate to the 1890s). But I had forgotten to cite which article this was, and instead of digging through my copious notes, I decided to run a search by homing in on particular words in the article and searching for it in the database. It wasn’t hard to find unique words: hmmm…how about “bayou st john” and “sluggish,” or “bayou st john” and “flat-chested.” I finally found it, after coming across ads to fix a “sluggish” liver, and ads (beginning in the 1920s) for various breast augmentation solutions.

Without further ado, here is a bit of poetry to brighten your day. It will brighten your day because it’s absolutely ridiculous, typifying the romantic language (not to mention values) that defined the period. At the moment this article was written, City Park was experiencing a renaissance after decades of ad hoc development punctuated by years of neglect. Within thirty years, it would largely resemble the City Park we know and love.

Lying between Canal street and Esplanade avenue, with the city cemeteries pressing close on one hand, with the sweet, sunlit spaces and gabled roofs of the old soldiers’ home on the other, with the cypress swamps of the lakeshore trooping up to the line fence like a horde of curious aborigines, with the bayou St. John [sic] and its sleepy sloops protecting it like a moat of old, with here and there a quaint Creole home close to its limits, the city park lies like a fallow field that will readily become a place of great beauty.

It is situated on a ridge as if here the flat-chested earth was swelled into a gentle mound. Across its width creeps the sluggish brown bayou Solage [sic], all choked with sedges and set like an illuminated missal with purple flag flowers and the delicate Holy Ghost lilies that flutter on their pale stalks like the ghosts of dead white butterflies chained to earth for their sins.

The greening grass wears here and there a delicate broidery of daisies, and the rough, seamed roots of thorn and oak are festooned with the pale grace of the southern wild violet, more lovely than any other in color. In the far corners heaps of blackberry vines shine like free skies set with white stars. [1]

Did you catch the horde of curious aborigines part? Or the dead butterflies chained to earth for their sins? This thing reads like a bad creative writing exercise. But thank you, Catharine Cole, for loaning us some words—perhaps more than we needed—since I’m fresh out!

1. “New Orleans City Park. A Bit of History as to What it Was in Olden.” Times-Picayune, 13 Mar. 1892,p.20. NewsBank, infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/image/v2:1223BCE5B718A166@EANX-NB-1228BBD6E62774C0@2412171-122671E8E84CFC70@19-1241C360DC863233@New Orleans City Park. A Bit of History as to What it Was in Olden?p=AMNEWS. Accessed 30 May 2017.

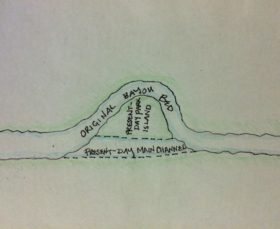

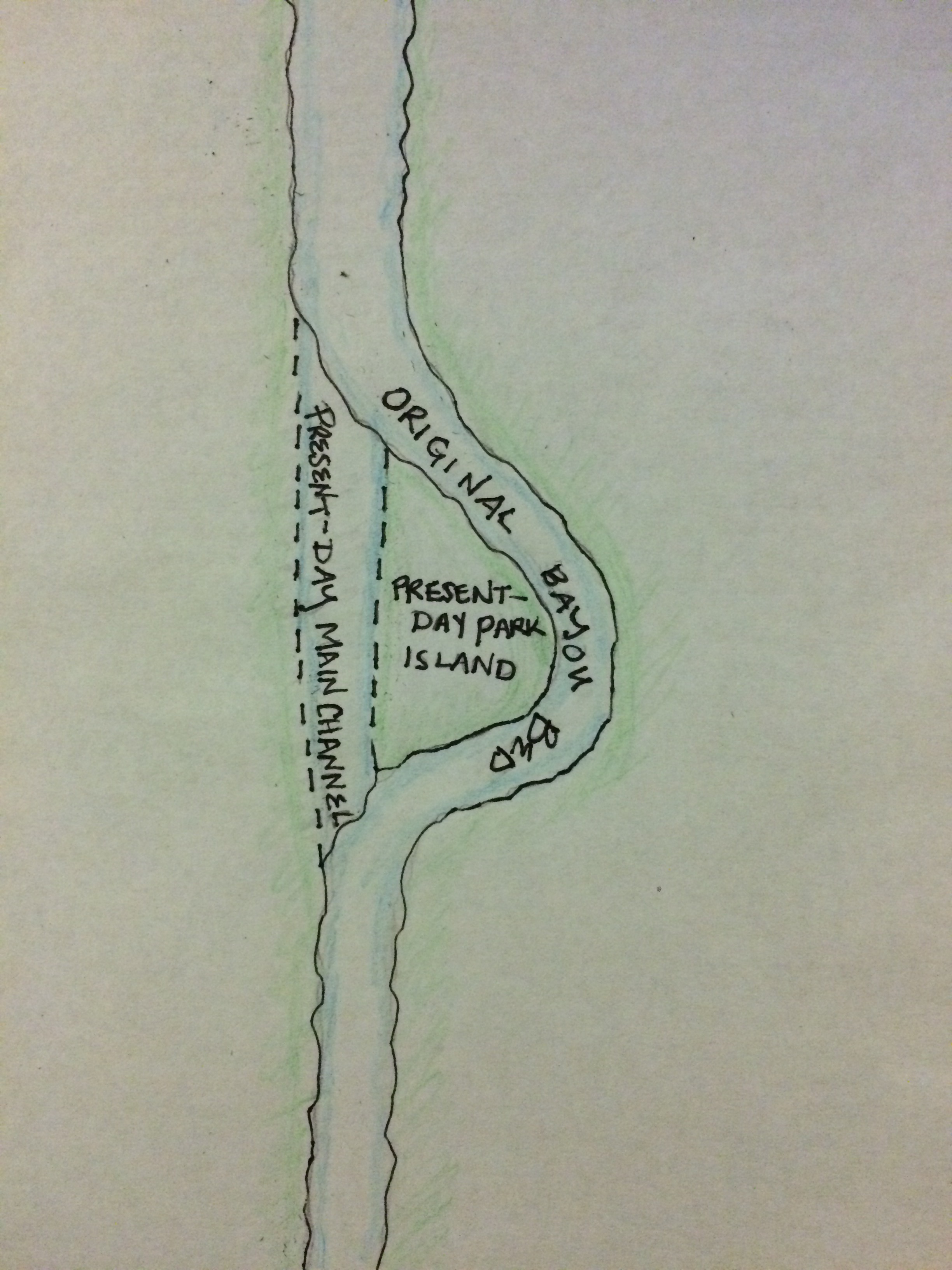

Which is all to say, I thought I knew something about the bayou and its island (singular).

Which is all to say, I thought I knew something about the bayou and its island (singular).

At last, we come to the surprising final act in the saga of Virginia Reed and Charles E. Letten. Finally we get to hear Reed herself speak! And her eloquence, as surely as it will win you over when you read an excerpt below, ultimately won over the judge in the case.

At last, we come to the surprising final act in the saga of Virginia Reed and Charles E. Letten. Finally we get to hear Reed herself speak! And her eloquence, as surely as it will win you over when you read an excerpt below, ultimately won over the judge in the case. Part two of the Virginia Reed embezzlement scandal (for part one, click

Part two of the Virginia Reed embezzlement scandal (for part one, click