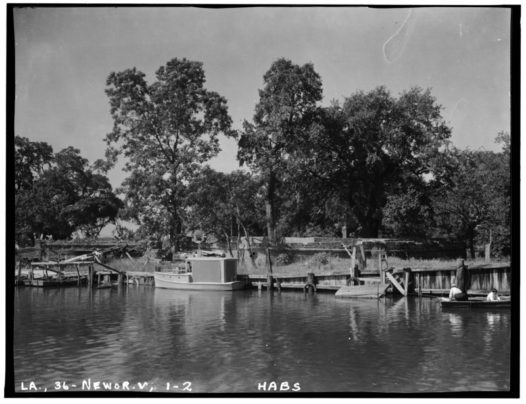

Bayou St. John near Spanish Fort

As I mentioned in my last post, the number of newspaper articles on Bayou St. John drowning victims I’ve come across in my travels continues to astound me. Victims of all ages, classes, and colors; victims of foul play, suicide, accidents, and mysterious circumstances. Even a waterbody as current-less and shallow as Bayou St. John can claim lives: water is water to those who can’t swim. Or, as in the case below, even to those who can.

For me, these articles are interesting for the stories behind them. Depending on the victim, a reader might get a nearly complete story—say, if the victim were sympathetic to those doing the telling (i.e. white, male, and at least somewhat respectable). Otherwise, we might only get a glimpse: a “pink calico dress” on the unnamed woman found in the bayou in 1852, for example. Or else we might get virtually nothing. Nothing beyond a dead body and various descriptors, depending on the time period, of his or her decidedly brown skin.

Below is one of the more vivid stories I’ve come across recently. What happened to young Quincy Koy, “expert swimmer,” in his improvised bathing suit? What could account for his inexplicable disappearance beneath the bayou’s slack surface?

“Good Swimmer Drowns—Quincy Koy Attempts to Cross Bayou St. John—Feat He Had Often Accomplished, and Disappears to Death Without Previous Warning:

“Within a few feet of his home and in full view of half a dozen people, Quincy Frank Koy, an expert swimmer, was drowned while attempting to swim across Bayou St. John yesterday at 3p.m.

“Young Koy…suggested yesterday to Thomas Maher, a younger boy…that the two take a swim in the bayou. The day being almost of summer temperature, the proposition was quickly agreed to, and, putting on improvised bathing suits, the two youths walked out in front of the Porteous home [where they both lived], which is at 1054 Moss Street…and waded into the stream.…

“Then Koy announced his intention of swimming across the bayou, which is about 150 feet wide at that place. Koy had performed the feat many times, and Maher thought nothing of the announcement….

“A few feet from the place where the boys were, Theodore Grunewald’s yacht Josephine was tied up. As the boys began their sport one of the members of the crew remarked sportively:

“‘Get the boat read [sic]; there is a boy getting ready to drown.’

“The other members of the crew laughed at the joke, little thinking that in five minutes they would actually lower a boat and go to strive with their might and main to save a drowning boy.

“Koy, when he struck out across the bayou, swam rapidly and easily until he had reached the middle of the stream. Without a cry or other sign that he was in distress the boy turned over on his back, floated for a moment on the water, and sank out of sight.…” [1]

Georges Montorgueil, 1857-1933 (creator) Henry Somm, 1844-1907 (illustrator)

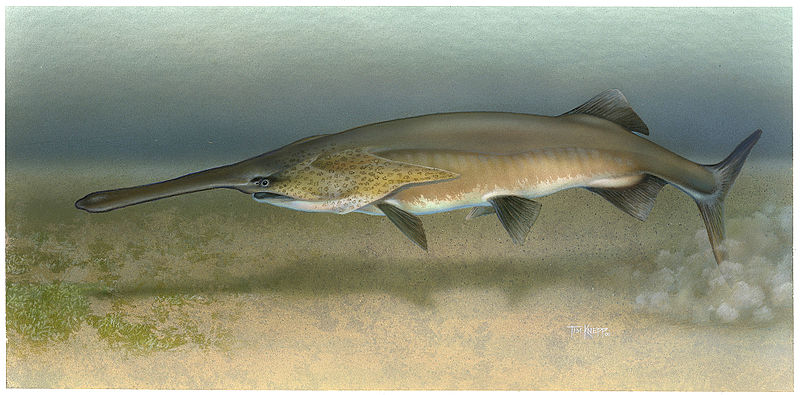

Georges Montorgueil, 1857-1933 (creator) Henry Somm, 1844-1907 (illustrator) So if you happen to take a swim in the bayou someday soon, don’t be alarmed if you feel something slippery slide against your leg! It’s only a sign of the bayou’s improving health, after all….

So if you happen to take a swim in the bayou someday soon, don’t be alarmed if you feel something slippery slide against your leg! It’s only a sign of the bayou’s improving health, after all….

These guys were the ones to remind me of that letter I came across while doing some bayou research at the New Orleans Public Library last summer. The letter was written by a certain Walter Parker, Chairman of the Bayou St. John Improvement Association (and future mayor of New Orleans), to Honorable George Reyer, Superintendent of Police, and dated April 10, 1934. It read as follows:

These guys were the ones to remind me of that letter I came across while doing some bayou research at the New Orleans Public Library last summer. The letter was written by a certain Walter Parker, Chairman of the Bayou St. John Improvement Association (and future mayor of New Orleans), to Honorable George Reyer, Superintendent of Police, and dated April 10, 1934. It read as follows: