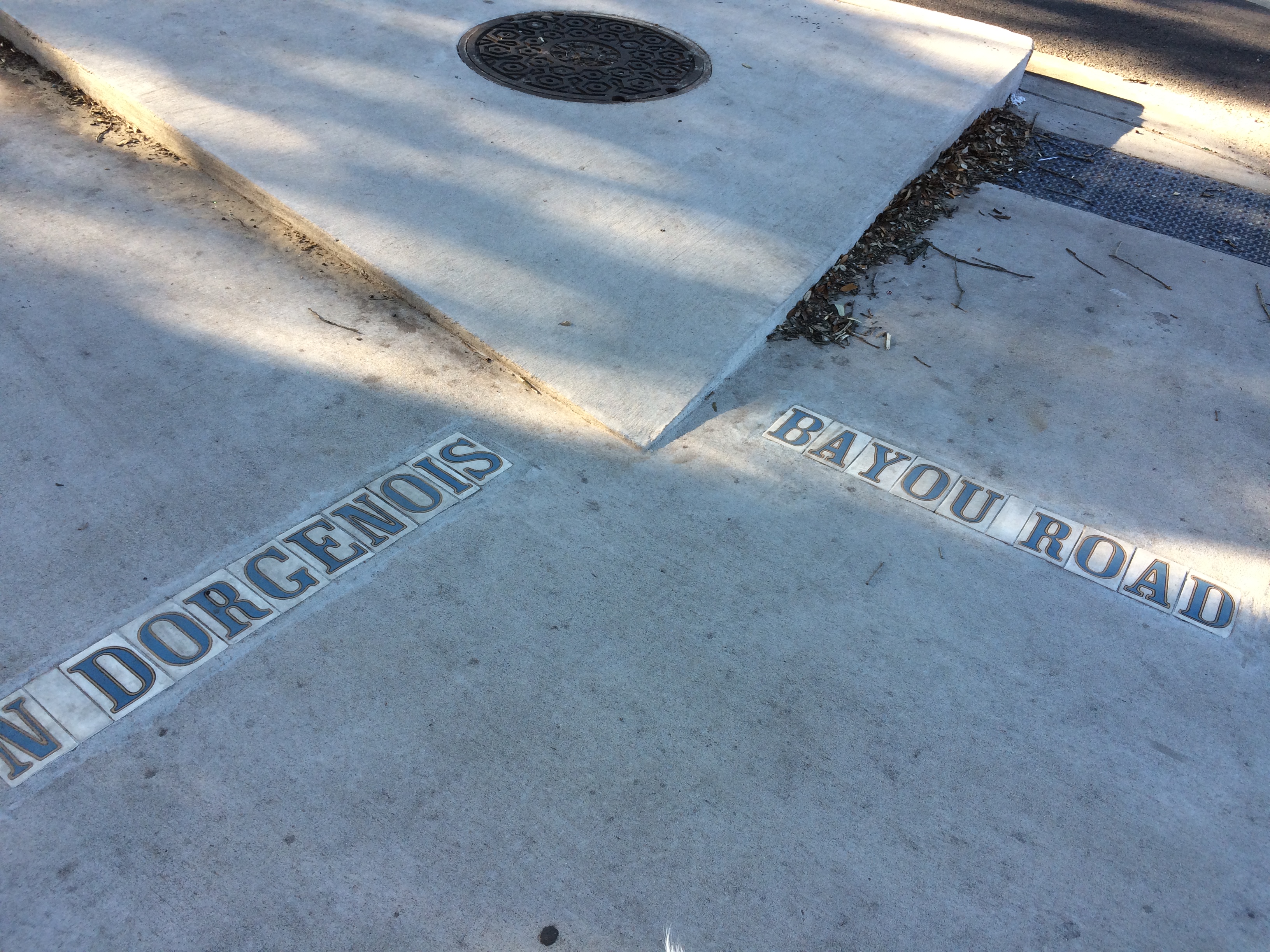

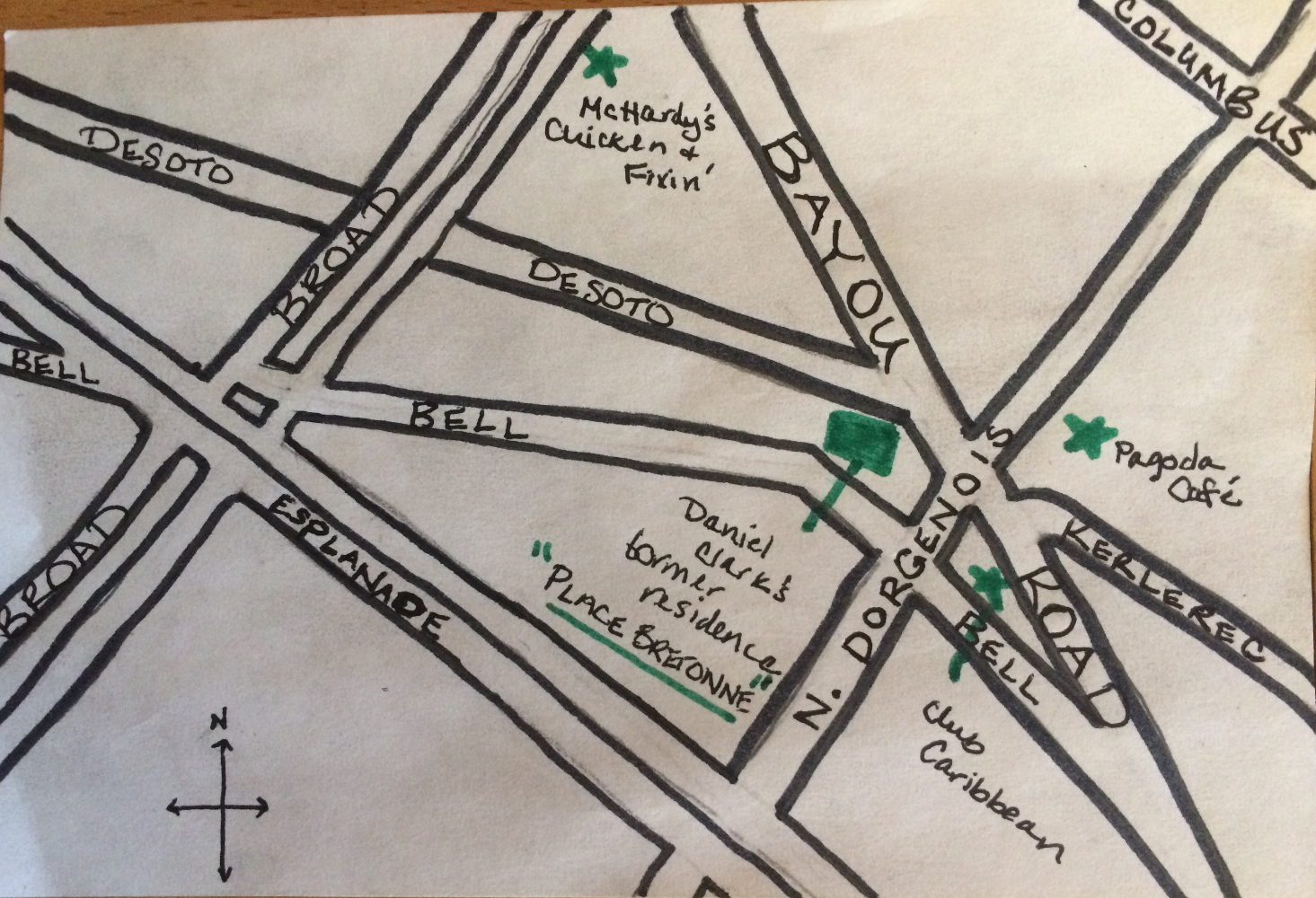

A couple weeks ago, I posted on my favorite New Orleans intersection: where N. Dorgenois, Bell, DeSoto, Kerlerec, and Bayou Road come together—that many-triangled flurry of streets that calls out to me as I walk my dog or pick up a breakfast burrito from Pagoda Cafe. As of my last post, I’d discovered that the site where the Church of I Am That I Am and King and Queen Emporium stands today was also site of the former home of Daniel Clark, prominent Anglo merchant of the Spanish period and the guy responsible for buying up a bunch of plantations between Dorgenois and Bayou St. John and mapping out Faubourg St. John in 1809. But, as I dug deeper, I discovered there was far more to learn….

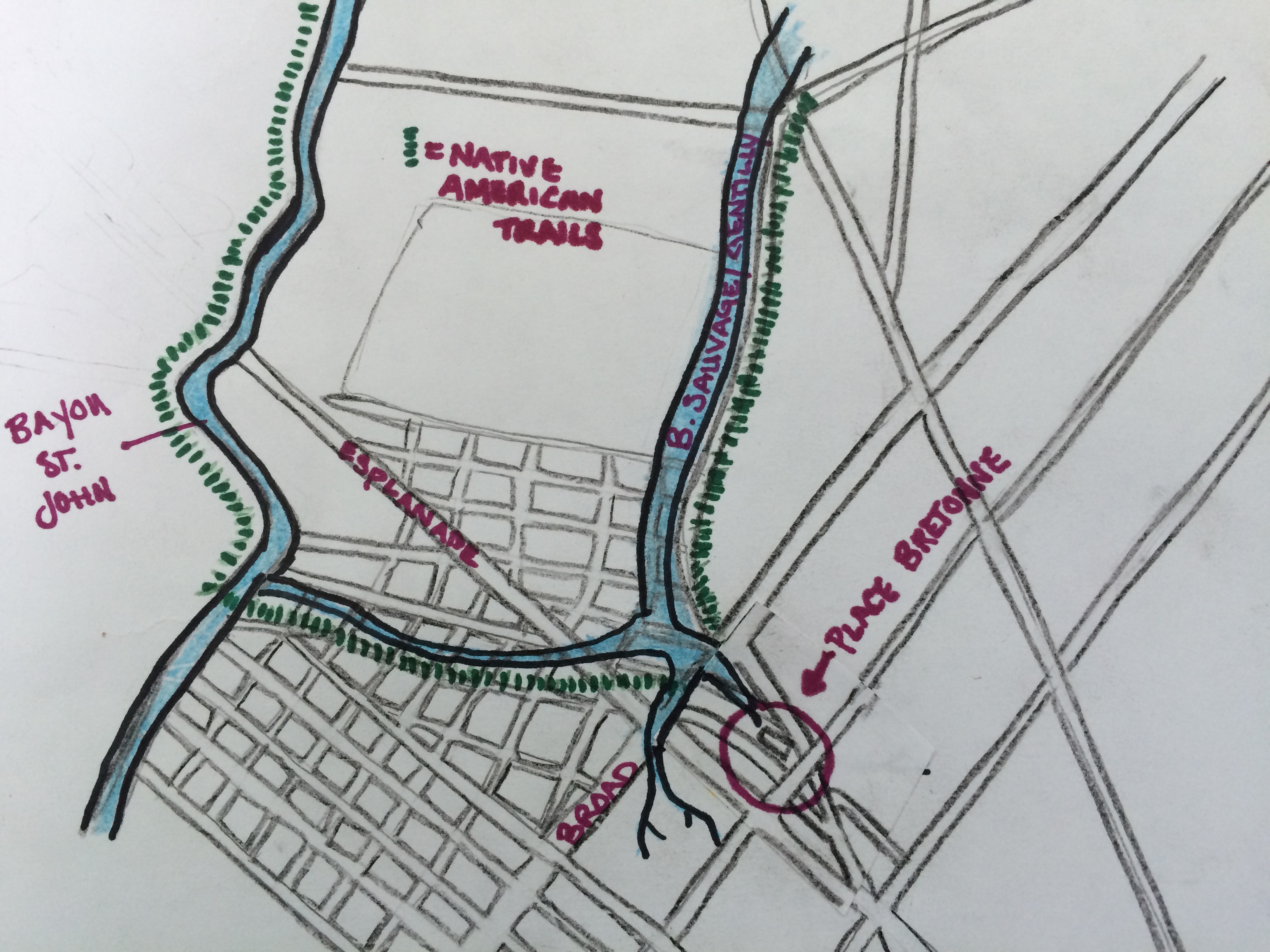

Based on colonial-era maps I’ve scoured, it looks like this intersection was the spot where two well-trafficked Indian trails merged from ancient times up until the French period. One of those was the path that led from Bayou St. John to the present-day French Quarter, that Bayou Road and Bell Street approximate today—the famous portage route that made New Orleans possible. The other path followed along Bayou Sauvage (or Bayou Gentilly, which followed the basic trajectory of present-day Gentilly Boulevard).

My most amateurish map to date! (Not to scale; everything is approximate.)

Based on written evidence and an appropriate dose of educated guessing, it would appear that where these paths came together, Indians from various tribes traded with one another—and this practice continued once Europeans arrived. According to historian Jerah Johnson, “New Orleans’ earliest, as well as its last, all-Indian market was held in an open area called the Place Bretonne at the conjunction of what are now Esplanade Avenue, Bayou Road, and Dorgenois, Bell, and DeSoto streets. It lasted, with gradually dwindling numbers of Indians after 1809 (when the opening of the Faubourg St. John separated it from Bayou St. John, which had been the main route the Indians followed into town), until the construction on that spot of the LeBreton Market building in 1867. Small groups of Indians still continued to sell goods there as well as in other parts of the city.”[1]

According to my research, Clark bought this parcel of land in 1804. He died in 1813 in his hip-roofed house that stood where the Church of I Am That I Am stands today. When he mapped out the future Faubourg St. John, he wanted this fan of streets to be the focal point of the neighborhood and called it “Place Bretonne.” Clearly, as Johnson mentions above, Clark’s decisions essentially closed off Native American trade connections between this site and Bayou St. John. After Clark’s death, the piece of land was sold to the city of New Orleans in 1836, and Johnson tells us a municipal market, called LeBreton Market, was then built on the site in 1867—which is the very same building the aforementioned church occupies today.

I’m still left wondering a bit about this site’s evolution. Did Clark, after buying up the land between Dorgenois and the bayou, simply build a house right where the Indian market had been? What did that look like when it was going down? And then what made the city decide to build a market there 60 years later, after the site had stopped being used for this purpose? Was its ancient past was well-known, and therefore the idea seemed obvious?

I don’t know yet whether there were more specific reasons for this evolution, but it seems to me that the Mississippi River might have everything to do with it. After it swung into its present channel, it left behind the Metairie-Gentilly ridge system that the Native Americans utilized, among many others, to traverse the landscape. Their movement along the ridges impacted the locations they chose for trade, and also influenced the founding of New Orleans in its present location. These pathways also influenced future streets (like Bayou Road) and plantation property lines like the ones that demarcated Clark’s land. Perhaps Clark wanted this site—an important intersection, a center of activity—for his own, and perhaps, after Clark was gone, the city recognized the site’s natural properties for what they were, and decided a municipal market simply belonged there.

LeBreton Market from Wikimedia Commons, 1938, by an uncredited WPA employee

LeBreton Market 1938, credits same as above photograph

Interior of LeBreton Market during WPA restoration, 1938; credit same as for above photographs

If any of you reading this know more about this intersection than I do, please reach out! All I know is the spot continues to buzz with energy—and now, when I walk my dog across Bayou Road’s brickwork, I can feel how ancient that energy truly is….

- Jerah Johnson, “Colonial New Orleans: A Fragment of the Eighteenth Century French Ethos” in Creole New Orleans: Race and Americanization, ed. Arnold R. Hirsch and Joseph Logsdon (Baton Rouge: Louisiana University Press, 1992) 39-40.