Imagine this: the year is 1730. You’re a 22-year-old clerk for the French Company of the Indies, and you’ve recently been sent from Paris to the new fledgling colony of Louisiana to be a bookkeeper in New Orleans, the colony’s capital. In what’s now the present-day French Quarter, a basic street grid extends a few blocks back from the river, populated by a handful of brick-between-post timber structures shellacked with lime made from crushed oyster shells. Untamed wilderness threatens to overtake the town from all sides. Un-penned pigs wander the streets. The air is thick with mosquitos. Here and there, crumbling ditches have been dug to help with drainage, but still—after a hard rain, the city streets blur into a series of shallow muddy lakes.[1] All around you, colonists are panicking. Violent conflicts between the French and the Natchez tribe upriver have set everyone on edge. At the tavern, talk of the Indians and slaves banding together and murdering colonists in their sleep is all you seem to hear. And yet, it’s Carnival season! And you’ve barely had alickof fun!

In 2004, The Historic New Orleans Collection acquired the unpublished manuscript of one Marc-Antoine Caillot, clerk for the French Company of the Indies, that details his time spent in New Orleans between 1729 and 1731. What resulted is a beautiful collaboration between Erin M. Greenwald, Teri F. Chalmers, and many scholars and researchers calledA Company Man: The Remarkable French-Atlantic Voyage of a Clerk for the Company of the Indies, published by The Historic New Orleans Collection in 2013. For anyone interested in this era of our city’s history, I highly recommend this book. For our purposes today, we’ll focus on the section of the manuscript devoted to a Lundi Gras celebration along the banks of—you guessed it!—our very own Bayou St. John!

Before we get to Lundi Gras, though, Caillot gives us a glimpse of what the area around Bayou St. John might have looked like in 1730: “At three-fourths of a league’s distance on the left you will find a hamlet called Bayou Saint John, where there live five or six inhabitants very rich in livestock.” Greenwald’s footnote explains: “In 1727 the population along Bayou Saint John totaled 121, including forty-one whites, three indentured servants, seventy-three blacks, and four Indian slaves.”[2]Caillot was probably referring to those several landowners that had settled their large concessions along the bayou’s banks in the early years of the 18th century, resulting in a rural “hamlet” consisting of those landowners’ families, servants, and slaves.

Ok, back to the Lundi Gras revelry. Caillot explains: “We were already quite far along in the Carnival season without having had the least bit of fun or entertainment, which made me miss France a great deal…. The next day, which was Lundi Gras, I went to the office, where I found my associates, who were bored to death. I proposed to them that we form a party of maskers and go to Bayou Saint John, where I knew that a lady friend of my friends was marrying off one of her daughters….”

Caillot explains that his associates were like, Oh cool, yeah that sounds fun…it’d be cool to crash the wedding party…but uhhh we don’t have anything to wear! and kind of lost motivation to make it happen. “But, upon seeing that no one wanted to come along, I got up from the table and said that I was going to find some others who would go, and I left.” Caillot couldn’t be deterred. “…I did not delay in assembling a party, composed of my landlord and his wife, who gave me something to wear. When we were ready and just about to leave, we saw someone with a violin come in, and I engaged him to come with us. I was beginning to feel very pleased about my party, when, by another stroke of luck, someone with an oboe, who was looking for the violin, came in where we were, to take the violin player away with him, but it happened the other way around, for, instead of both of them leaving, they stayed. [Doesn’t this sound like just the kind of Carnival fortuitousness we’re used to in modern-day New Orleans?! An impromptu party, and then some guy with a guitar just happens to walk by….] I had them play while waiting for us to get ready to leave. [Oh, we all know this story: the hours and hours it takes for everyone to get out of the house and to the parade!] The gentlemen I had left at the table…came quickly upon hearing the instruments. But, since we had our faces masked, it was impossible for them to recognize us until we took them off. This made them want to mask, too, so that we ended up with eleven in our party. Some were in red clothing, as Amazons, others in clothes trimmed with braid, others as women. As for myself, I was dressed as a shepherdess in white. I had a corset of white dimity, a muslin skirt, a large pannier, right down to the chemise, along with plenty of beauty marks too. [Love the attention to detail. This is what a good Carnival costume requires.] I had my husband, who was the Marquis de Carnival; he had a suit trimmed with gold braid on all the seams. Our postilion went in front, accompanied by eight actual Negro slaves, who each carried a flambeau to light our way. It was nine in the evening when we left.” [3]

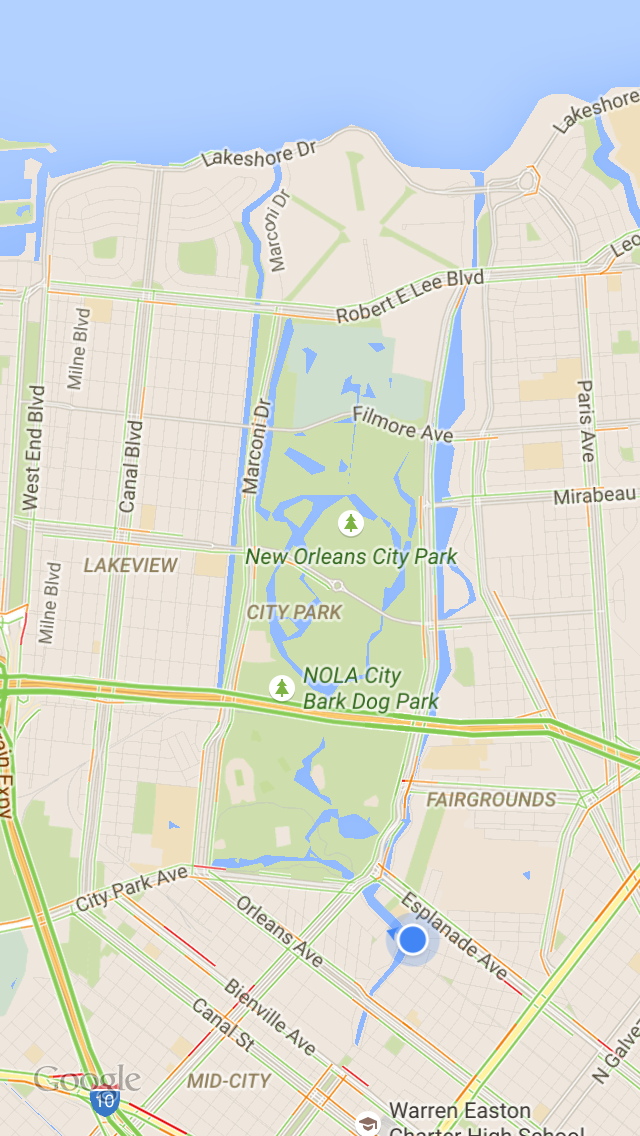

On the way to the bayou, presumably along the path occupied by present-day Bayou Road, the travelers came upon several bears, which they scared away with the flambeaux. When they got to the bayou, they sent a slave to go check out the wedding party and see what was going on—as in, are they done with all the boring parts yet? Are they dancing yet or not?

The slave returned with the news that, yes, they had just begun dancing. “Right away, our instruments began playing, the postilion started cracking his whip, and we walked toward the house where the wedding celebration was taking place.” Caillot goes on to describe the wedding party receiving them with excitement, requesting that they join in and dance, and then forcing them to finally remove their masks. Everyone was recognized very quickly, aside from our cross-dressing young friend: “What also made it hard for people to recognize me was that I had shaved very closely that evening and had a number of beauty marks on my face, and even on my breasts, which I had plumped up. [!!!] I was also the one out of all my group who was dressed up the most coquettishly. Thus I had the pleasure of gaining victory over my comrades, and, no matter that I was unmasked, my admirers were unable to resolve themselves to extinguishing their fires, which were lit very hotly, even though in such a short time…”[4]. Our narrator was so sexy and convincing as a lady, the menfolk in the crowd were hard pressed to “extinguish their fires”!

To hear more about the festivities that took place on this 1730 Lundi Gras, and to experience more of Caillot’s adventures, go findA Company Man. And when you go out this Lundi Gras, perhaps you’ll plump your breasts with a little extra gusto—and contemplate, on your way to the parades, some of the ingredients of our city’s founding: the violence, the distribution of power, the bizarre revelry….

1. Lawrence N. Powell, The Accidental City: Improvising New Orleans (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2012) 66-68.

2. Marc-Antoine Caillot, A Company Man: The Remarkable French-Atlantic Voyage of a Clerk for the Company of the Indies, ed. Erin M. Greenwald, trans. Teri F. Chalmers (New Orleans: The Historic New Orleans Collection, 2013) 82.

3. Caillot, A Company Man, 134-135.Caillot, A Company Man, 135-136.