Did you know that where the Pitot House and Desmare Playground sit now was once a 19th century pleasure garden called “the Tivoli”? Leonard Victor Huber in his New Orleans: A Pictorial History even calls it New Orleans’ first park. At that time, the area around the bayou was seen as a rural escape from the hustle and bustle of city living and boasted several pleasure gardens by the end of the 19th century—green spaces where residents could dance, drink, and mingle in true New Orleans fashion.

Pitot House

Field behind Desmare Playground

Edna Freiberg, in her book Bayou St. John in Colonial Louisiana 1699-1803, includes a description of Tivoli patrons by a Mr. John F. Watson, a Philadelphia man visiting New Orleans in 1804. He tells us how those visiting the garden would “walk out in the dust and walk home after ten o’clock at night” (I picture ladies in their finery trudging along Bayou Road, although I’m not exactly sure what he means here). He also mentions ladies “of the best families” dressed to the nines, arriving at the gardens in their ox carts. [1]

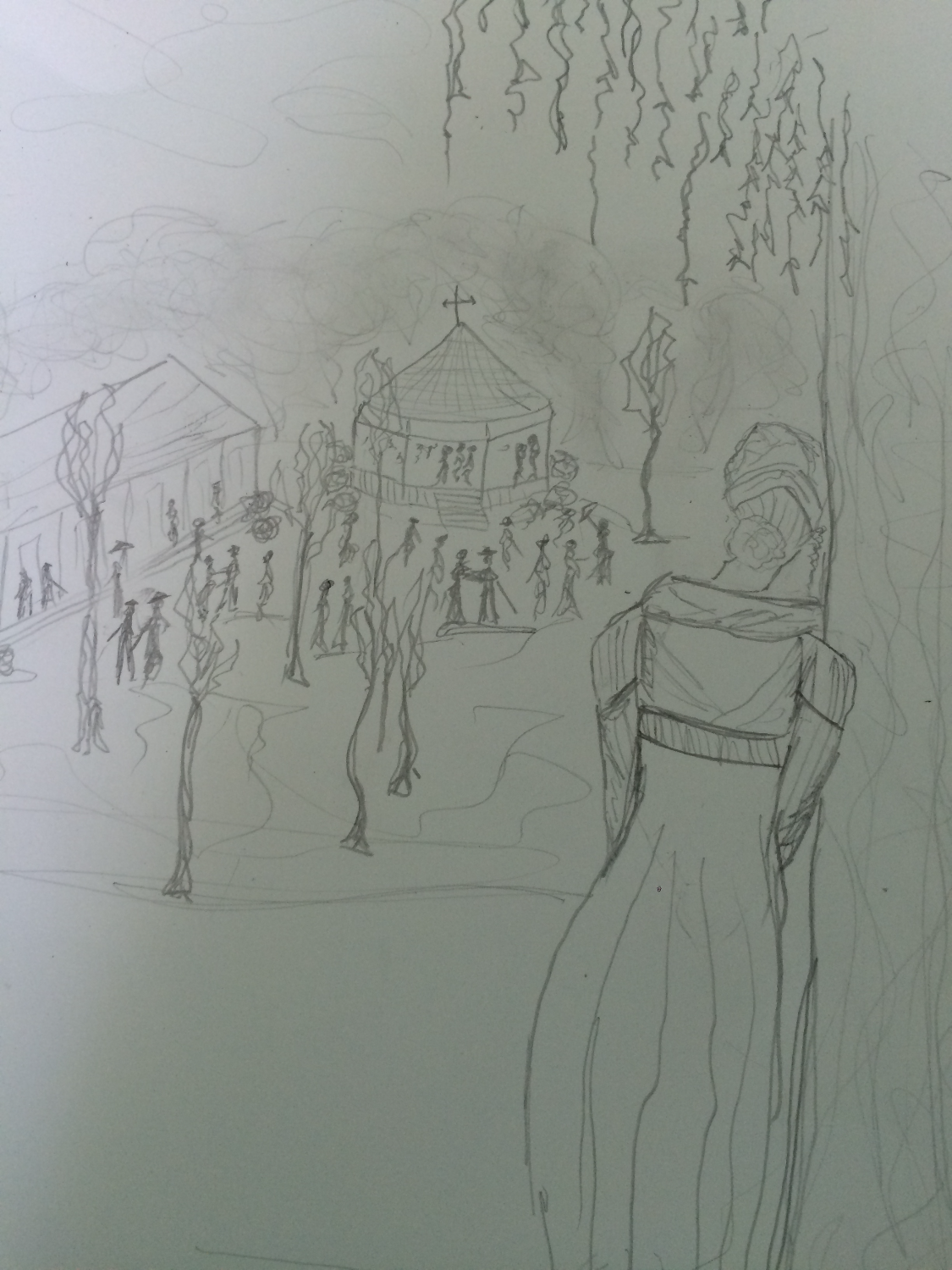

LSU professor Lake Douglas, in his fascinating book Public Spaces, Private Gardens, quotes another traveler to New Orleans in 1806, the Irishman Thomas Ashe: “Every Sunday evening, ‘all the beauty of the country concentrates, without any regard to birth, wealth, or colour…. The room is spacious and circular; well painted and adorned, and surrounded by orange trees and aromatic shrubs, which diffuse through it a delightful odor. I went to Tivoli, and danced in a very brilliant assembly of ladies.’” [2]

Douglas goes on to highlight Ashe’s phrase “without any regard to birth, wealth, or colour,” which speaks volumes when put into the context of Ashe’s wider study of 19th century New Orleans’ social customs surrounding gender, race, and class—which were complicated to say the least, and which could often be observed in microcosm in the city’s dance halls. More on this to come: I am attempting to learn more about Ashe, New Orleans’ “quadroon balls,” and the city’s relationship to race and gender more generally as it transitioned into the 19th century.

For now, I’ll just do a little poetic imagining. Beneath the traffic sounds of Esplanade, can you still hear the clopping arrival of those ladies in their ox carts? Can you smell the orange blossoms? Can you see the circular, lantern-lit pavilion set amongst the trees, and the couples strolling about in their fancy hats and walking canes and rustling skirts? When you look up, can you see the stars beginning to emerge around the edges of the evening clouds? Can you hear the music warbling in the breeze, distorted by the passage of hundreds of years and layers upon layers of history?

(This is me, hiding behind a cypress tree, imagining myself into the scene. I even put on my early 19th century dress with the high waistline for the occasion! Don’t ask me where the hill I’m standing on came from….it’s an illusion. I don’t have an ox cart (Uber?? Where are you??) so I’ll have to walk along Bayou Road to get home….)