These bayou posts have become a way for the two sides of my writing life to converge: the history and the poetry, the “reality” and the imaginary. See below for an example of what I mean.

My favorite part of Sherwood Gagliano’s “Geoarchaeology of the Northern Gulf Shore” is when he talks about natural systems: “Natural systems are defined by recurring patterns of flow of energy and materials on, or near, the earth’s surface. These energy flows or fluxes are most commonly in the form of fluid movement (water, ice, wind, etc.) but may also be through chemical processes. Energy flow is the integrating factor that defines the natural system.”[1 ]In New Orleans, we are part of a deltaic coastal “cascading system.” We live at a point of interaction between deltaic and coastal forces—where fresh water and salt water meet: “a chain of systems…dynamically linked by a cascade of energy.”[2] This energetic formula defines our geography, and therefore our history. I love the word “energy” because it’s both scientific and whimsical in its usages. Another convergence. Let’s follow it!

Around where the Bayou St. John meets Esplanade Avenue, near the entrance to City Park: this place is its own energetic system, according to me. The phenomena, geological and historical, that have unfolded at this location over the last few thousand years have charged it up so much that next time you’re there—crossing over the bridge to go to the NOMA, for example—you might be able to feel it. Let me give you the briefest of brief histories about this particular spot:

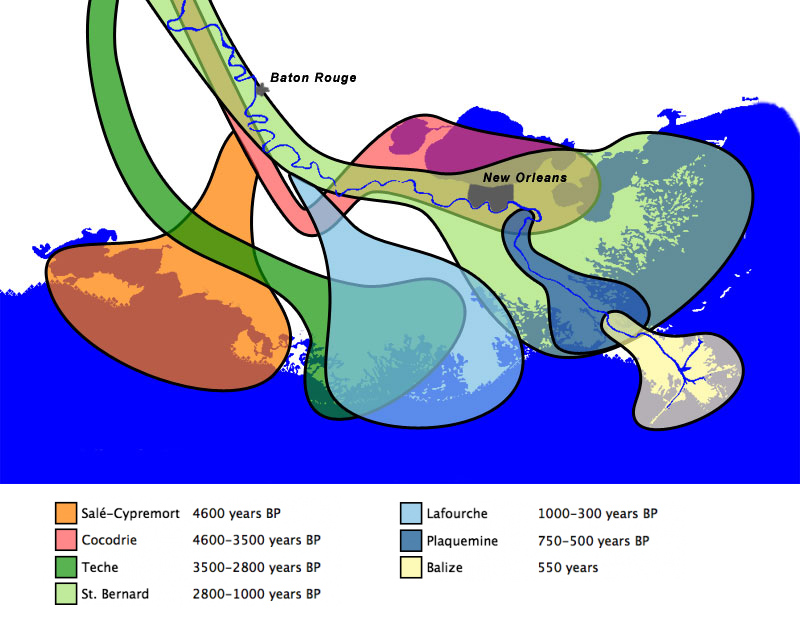

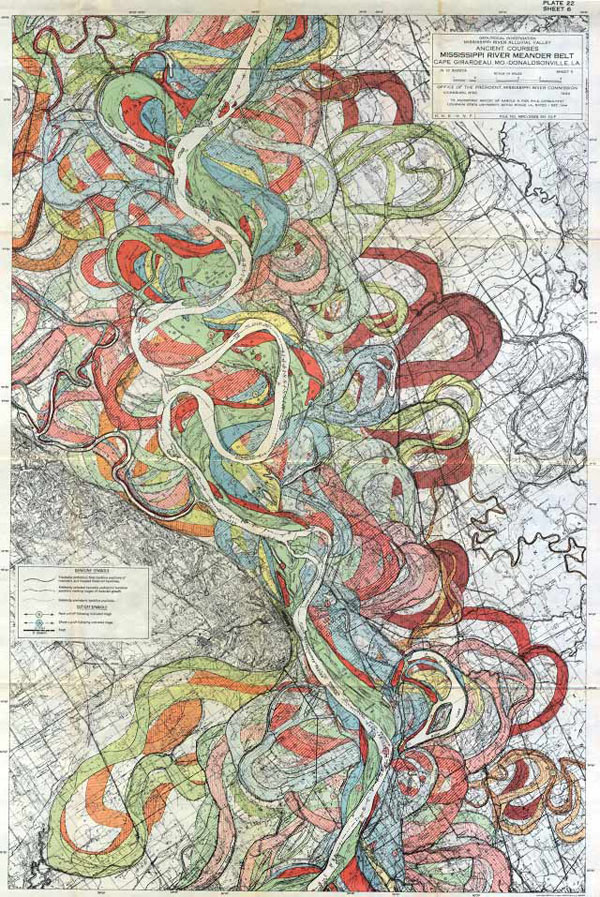

When the planet warmed after the last ice age, the frozen water that had spread across our continent began to melt, flushing into a massive declivity in the landscape called the Mississippi Embayment and flowing down to the Gulf, bringing with it monumental amounts of sediment. The sediment accumulated until it rose up out of the sea and formed its own land. Anywhere this proto-Mississippi River went, it built the land beneath itself higher and higher. Eventually, with the help of gravity, it would slice through its own banks and find a more direct path to the sea. In this way, the Mississippi has been building and swinging, building and swinging, for thousands of years. For a while, before it swung toward its current path 700 years ago, a main arm of it flowed west to east from present-day Kenner, through the heart of New Orleans, out to present-day New Orleans East.[3]

They call this, among other similar names, the Metairie-Sauvage distributary. This former limb of the Mississippi River is crucial to our tale. For one thing, it built up the relatively high, well-drained Metairie-Gentilly ridge system (which, along with the Esplanade Ridge, was crucial to our city’s early history) through the alluvial process outlined above. It also spawned (gasp!) the bayou itself! Near where modern-day Esplanade Avenue nears City Park, this former distributary meandered…sharply. No one quite knows why it did, but we do know that in the process of meandering it sent yet another distributary southward (a body of water simply called the Unknown Bayou, that would eventually form Esplanade Ridge) and another, smaller distributary northward, toward the lake (the Bayou St. John!). For some inexplicable reason, the Metairie-Sauvage distributary split into three, irregular fingers at this location—and thank goodness it did!

Here’s another theory about the bayou’s birth, since what I’ve explained above is not 100% certain: it’s possible that after the Mississippi chose its current path 700 years ago and the Metairie-Sauvage course was abandoned, becoming a sluggish bayou in the process, the Bayou St. John formed as a drainage conduit for this larger bayou. At a weak point in the natural levee (around where present-day Esplanade nears City Park!) the Metairie-Sauvage flood waters crevassed and flowed toward the lake, a process that would repeat itself until the bayou was gouged permanently into the landscape. It’s possible, indeed probable, that the formation of the bayou is a combination of these theories—a drainage conduit throughout the millennia, if you will.

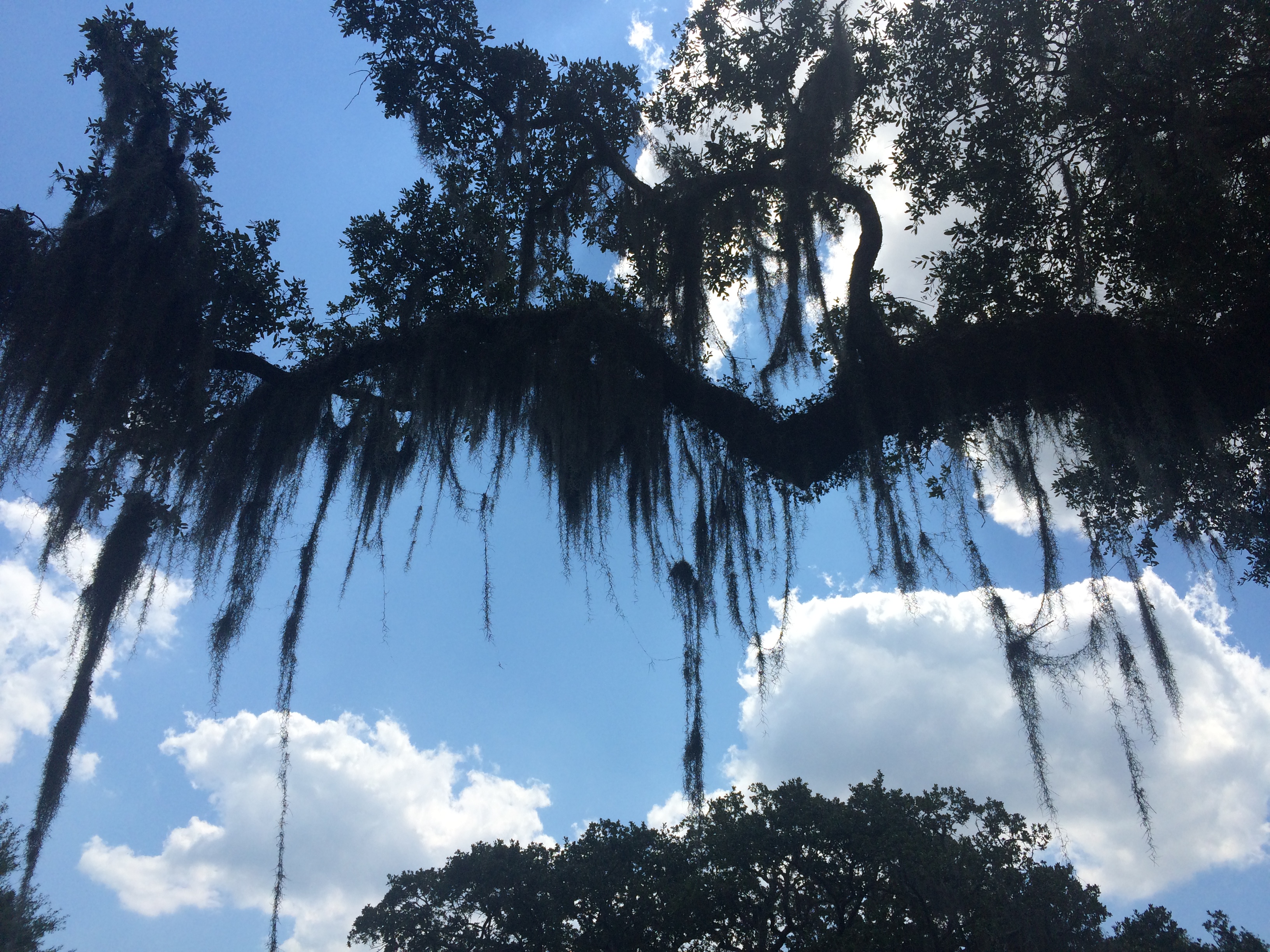

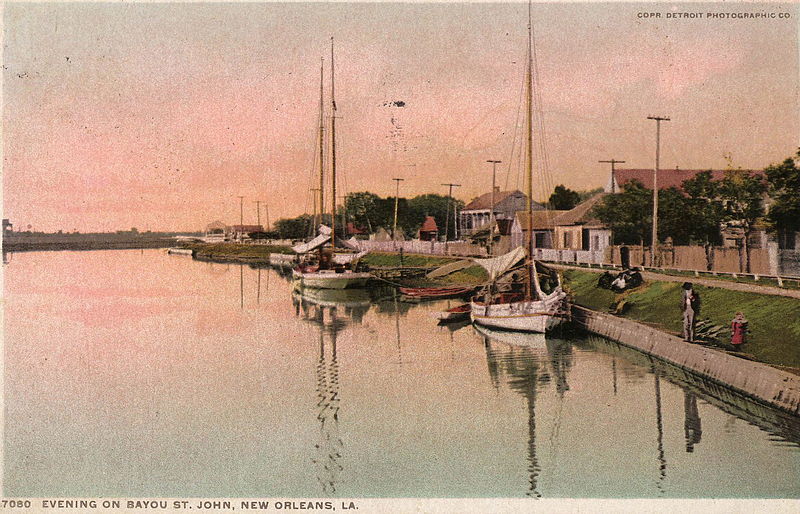

Either way you slice it, this spot—near where City Park Avenue meets Carrollton at Moss, near the roundabout with P.G.T. Beauregard at its center, near where the bridge spans the bayou and oak-lined Esplanade begins—has seen a lot of prehistoric action. Water trickling, gushing, overflowing, bifurcating—to the north, to the southeast, to the east. Water heaping up and creeping through. It’s seen a lot of historic action as well. Did you know, for example, that in 1908 they removed the bridge that spanned the bayou at Esplanade to make way for a larger bridge, more accommodating to automobiles, and that after they removed it, they strapped it to a barge and floated it down to a spot just across from present-day Cabrini High School? That’s right: our iconic Magnolia Bridge was once at Esplanade Avenue. And did you know that in the construction of this new fancy bridge at Esplanade, there was a tragic accident and the thing collapsed and fell, killing and injuring workers on its way down?

Yes, this mini energy system is roiling indeed. See if you notice it next time you’re there!

Where City Park Avenue intersects Carrollton Avenue at Moss Street. photo by author

The bayou, riverside of the Esplanade bridge. photo by author

The Esplanade bridge looking toward the entrance of City Park. photo by author