And now for some completely disparate events, united only by location (but come on: location is everything).

From The Times-Picayune, May 31, 1844:

“A STRANGE DUEL BLOCKED.—Two girls of the town, with their seconds who were also girls, were yesterday arrested by the police when about to fight a duel, with pistols and Bowie knives, near Bayou St. John. Finding they would not be allowed to endanger each others lives according to approved and fashionable rules, the belligerents had a small fightau naturel—or in other words, set to and tore each others hair and faces in regular cat and dog style. They are all in the calaboose.” [1]

Oh, to know more about these women and their interpersonal issues! Bowie knives!?! The newspaper seems to find this storyquiteamusing, and I swear there’s a hint of voyeurism in that “au natural,” but maybe I’m just imagining things….

From The Times-Picayune, September 19, 1847:

“Inquest.—Coroner Spedden was last evening called upon to hold an inquest on the body of J. Hoit, who was found in the Bayou St. John, opposite the draining company’s building in the Third Municipality. The face of the deceased was greatly disfigured, almost all the bones being broken or crushed, and there was a gash across his throat. The body was genteelly dressed, having on a black frock coat and pantaloons. Many papers were found upon his person, among them some letters of introduction to some of our citizens, and a letter written by himself addressed to his wife residing in the state of New York. In this letter, in which $10 were enclosed, he said that having just arrived he knew but little of the city, as he had not yet left the vessel by which he came, and would write again soon. This letter was dated on the 11th inst. [present month] There can be no doubt the deceased came upon his death by violence, and a verdict was rendered in accordance with the above facts. This case calls loudly on the authorities for the most thorough investigation. We would urge it upon their immediate attention.” [2]

Ok, which of my friends is going to write a short story about this genteel murder victim? Poor guy.

And now for some more contemporary action:

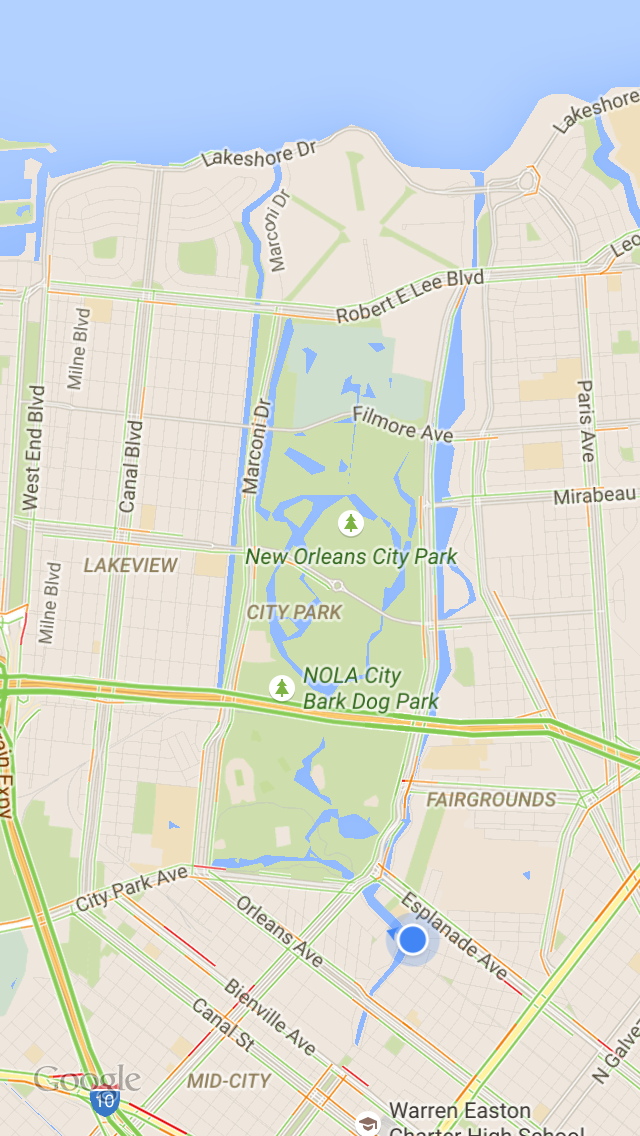

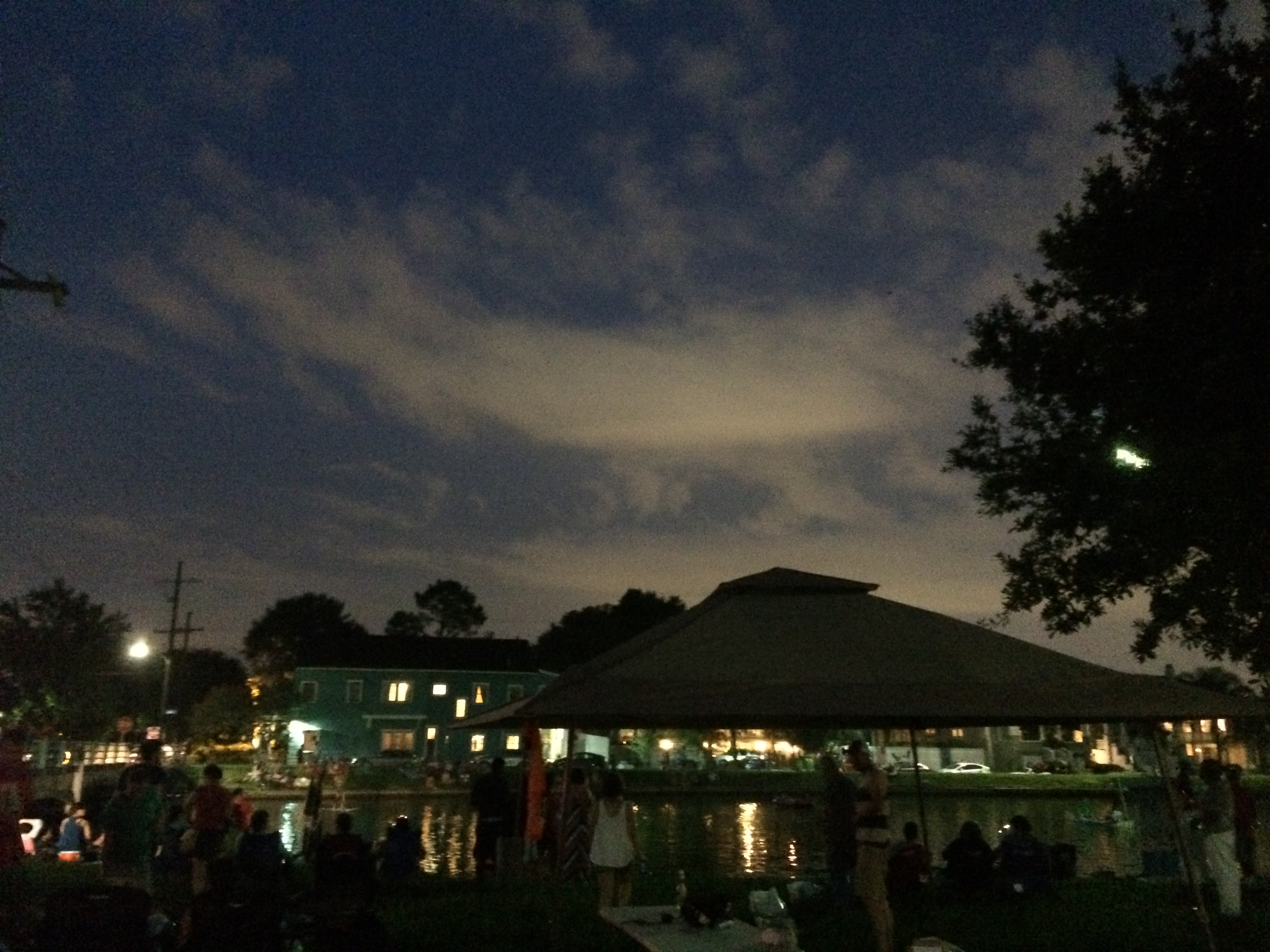

The Krewe of Kolossos 4th of July Flotilla on the bayou! DIY rafts, illegal fireworks (unconnected to the krewe, I think) and much revelry.

I was a little late and so missed most of the rafts, but I caught Giraffe Raft.

Fireworks set off among power lines and large crowds without the fire department present=terrifying AND exhilarating.

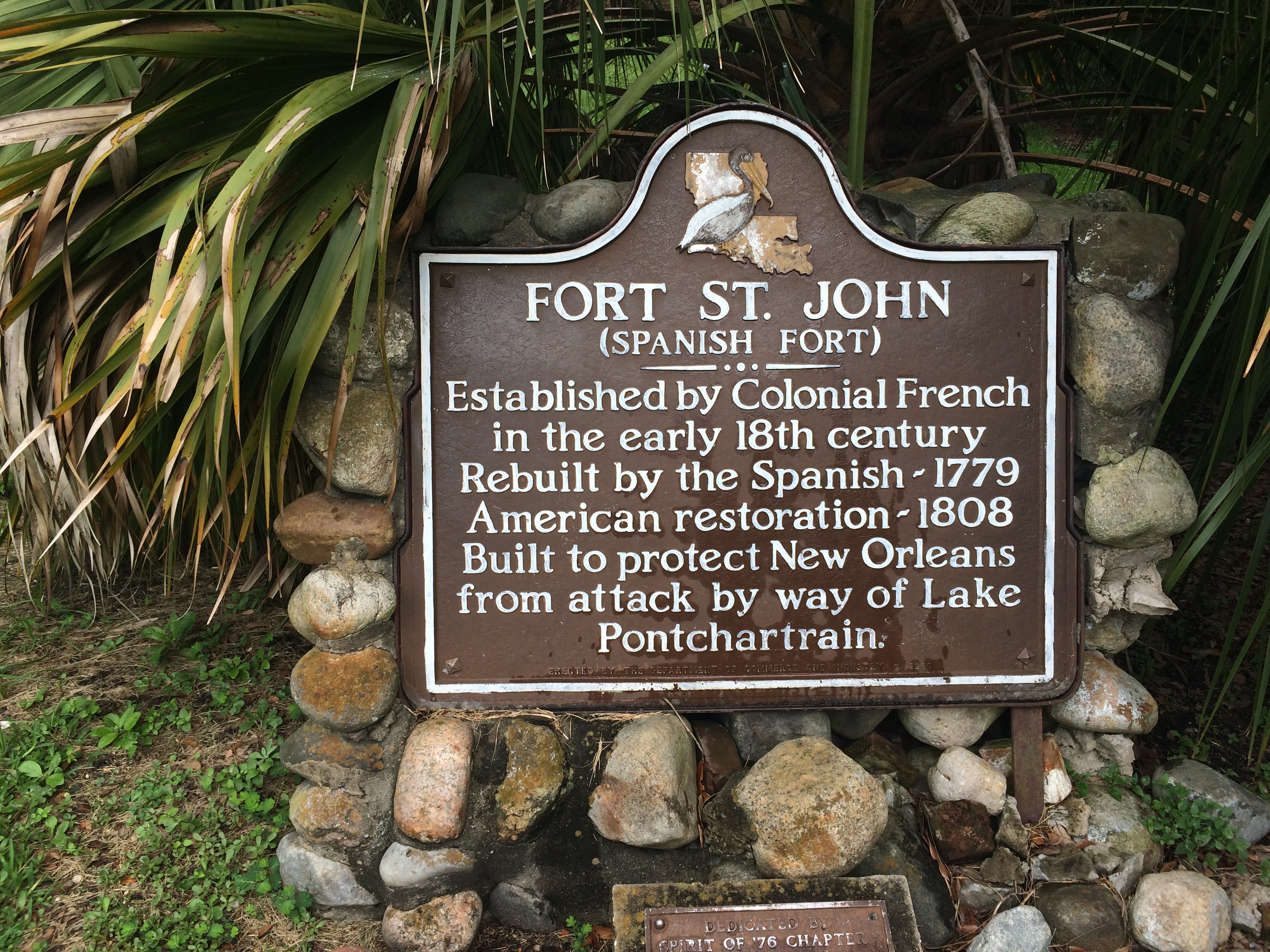

Imagine: each of the above events—violence, mystery, celebration—occurred over the course of a few hours, or maybe only a few minutes, within the span of the city’s history. I love thinking about all the action this sluggish water body has witnessed, once the city was built up around it and well before that time—between when it formed itself out of the Mississippi’s flood water (there are a couple theories out there about the bayou’s birth; this is one of them), became an important trade route for nearby Indians, and eventually saw the arrival of Colonial powers. That’s pretty impressive for a four-mile-long, hardly-flowing finger of water among a massive network of lakes, rivers, streams, canals, and many, many others bayous—a tiny rivulet in a veritable world of water….

1. “A Strange Duel Blocked.” Times-Picayune 31 May 1844: 2. NewsBank. Web. 13 Jan. 2016.

2. “City Intelligence.” Times-Picayune 19 Sep. 1847: 2. NewsBank. Web. 13 Jan. 2016.

<

<