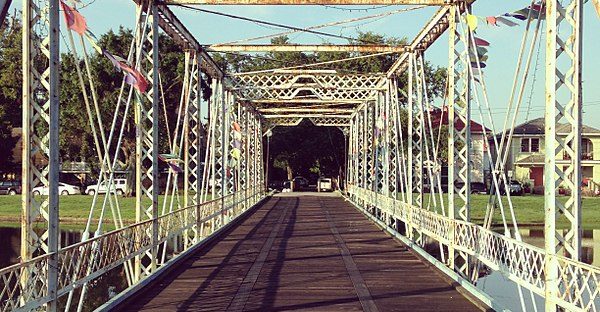

Since both author Cassie Pruyn and the iconic Magnolia Bridge have much to look forward to in the coming months, they thought it would be a good idea to get together and chat. The following conversation took place on Saturday, November 25th, 2017, on the banks of Bayou St. John.

Cassie Pruyn (CP): First of all, Ms. Bridge—

Magnolia Bridge (MG): Please! Call me Mag.

CP: Ok, Mag. First of all, congratulations on your upcoming $1.3 million renovation, scheduled to begin in January. You must be thrilled!

MG: Thank you, Cassie. And congratulations to you on the release of your book on the history of Bayou St. John! Yes, I’m totally psyched about the reno. It’s been a long time in coming, and the area’s civic organizations, together with City Councilwoman Susan Guidry, have worked tirelessly to get it going. Obviously, this won’t be my first renovation. The WPA reno in 1937 still brings back fond memories. But this one is much-needed, and I’m really looking forward to getting my substructure repaired, among other things.

CP: I’m really looking forward to setting foot on your repaired decking, and seeing your new paint job (not that I don’t love the cool “distressed” look you’ve got going on currently!).

MG: Thanks. I will be nice to feel the love and care the city still has for me after all these years.

CP: Speaking of “all these years,” why don’t you remind us how you came to be Bayou St. John’s most iconic bridge?

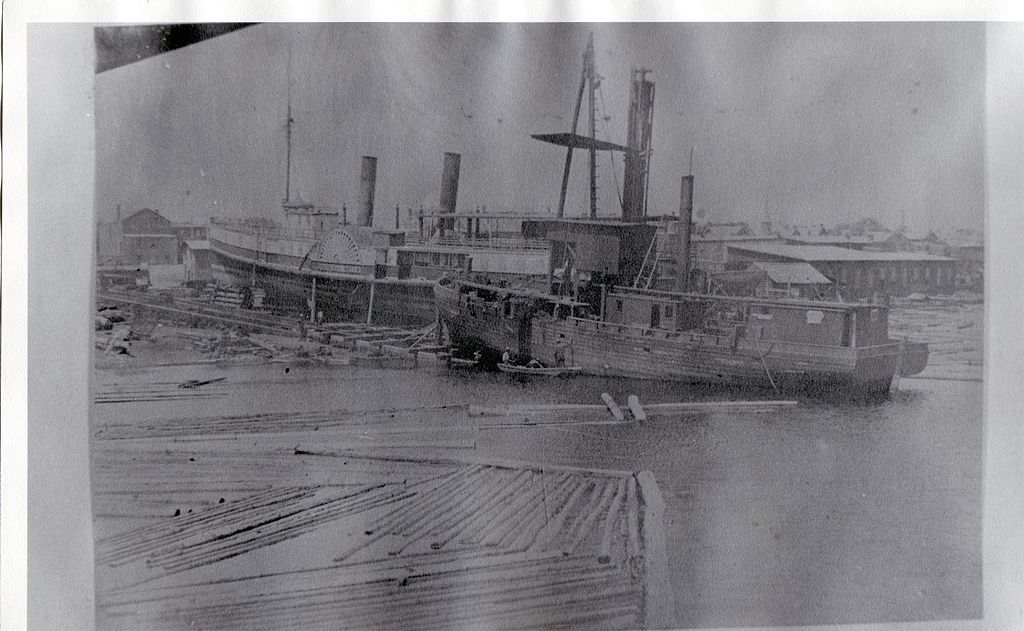

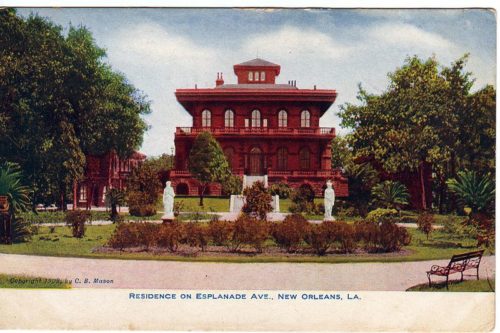

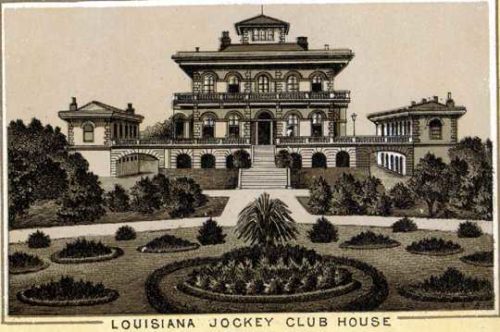

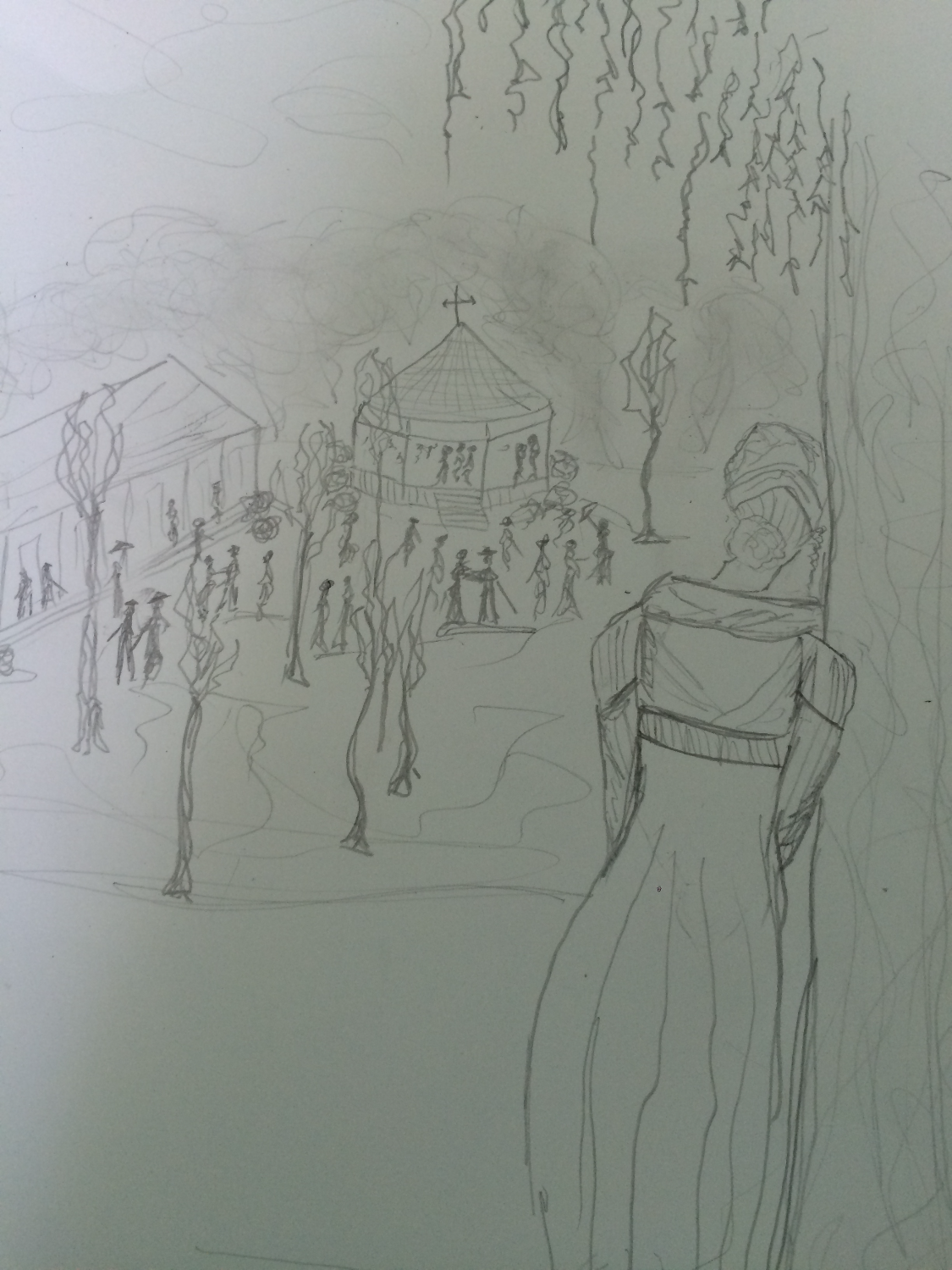

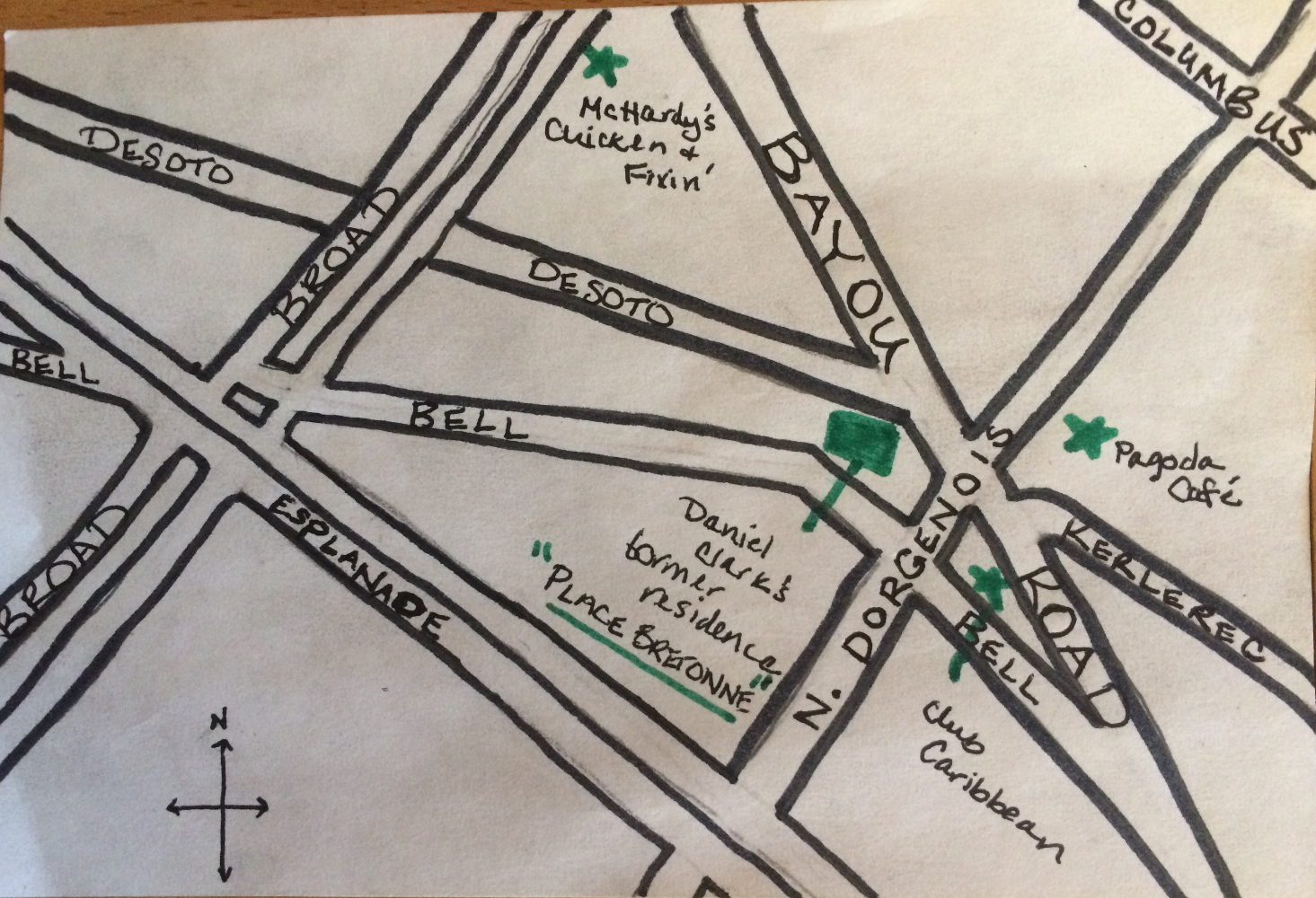

MG: Well, it all started some time in the latter half of the 19th century. Alas, I’m embarrassed to say I don’t remember the exact date. But back in those days, I was the bridge at Esplanade Avenue—I served as that all-important connective link for years, which many residents may not realize. Oh, the traffic I used to see back then! Horses and buggies, that sort of thing. Later, big lumbering streetcars. I know, just the thought of something that heavy crossing these splintery planks gives you the shivers, but back then I could handle it. Soon, automobiles were crossing my span, and alas—I just wasn’t big enough to support the increase in traffic at that location. So, in 1908, to make way for the new bridge (which—and this is kind of petty to say—that thing not only collapsed while they were building it, actually killing someone, but it also broke just a few years later! A terrible design, but I won’t go into it….), they floated me down to my current location, where I replaced an old footbridge that used to be here. And I’ve been here ever since.

CP: Amazing.

MG: Ok, enough about me! I’m really excited to talk about your newly-released book on the history of Bayou St. John! I hear I’m featured on the cover in my original Esplanade Avenue location—are the rumors true?!

CP: That’s right! The book, which is a comprehensive history of Bayou St. John (the first of its kind) comes out on November 27th. I’ll have a launch event at Octavia Books on Sunday, December 10th, at 2pm, and another at Fair Grinds on Saturday, December 16, from 9:30-noon. I know those are going to be tricky for you to make, but I’ll be sure to drop by and give you a copy. And yes, you are indeed featured on the front, looking really elegant in black-and-white….

MG: Cut it out! I’m blushing! Give us a bit of context for this project. What brought you to it, and what’s the journey been like?

CP: Sure. Around 3 years ago or so, a friend urged me to take this project on. As a poet who’s always been interested in history, bodies of water, and the intersection of the two, I just couldn’t say no. I learned a lot along the way, needless to say, and got lots of help and support from local institutions, experts, and folks in the community. It was such a fun and challenging project, and it’s a true honor to be handing it over to readers on the eve of the city’s Tricentennial celebration in 2018. I couldn’t be more excited!

MG: Me either! I can’t wait to learn more about this waterway that’s been flowing beneath me for close to 150 years now—that’s going to be really special for me. Where can folks get more information about the book?

CP: Interested readers can visit The History Press to purchase the book, and can check out my blog series on the the bayou’s history over at ViaNolaVie, as well as right here on my website.

MG: Awesome! I don’t spend much time online, but if I did….

CP: I get it! No worries, Mag. Listen, it’s been nice chatting with you! Good luck on all the big changes awaiting you. And keep in touch!

MG: I’ll be here whenever you want to stop by. See you around!