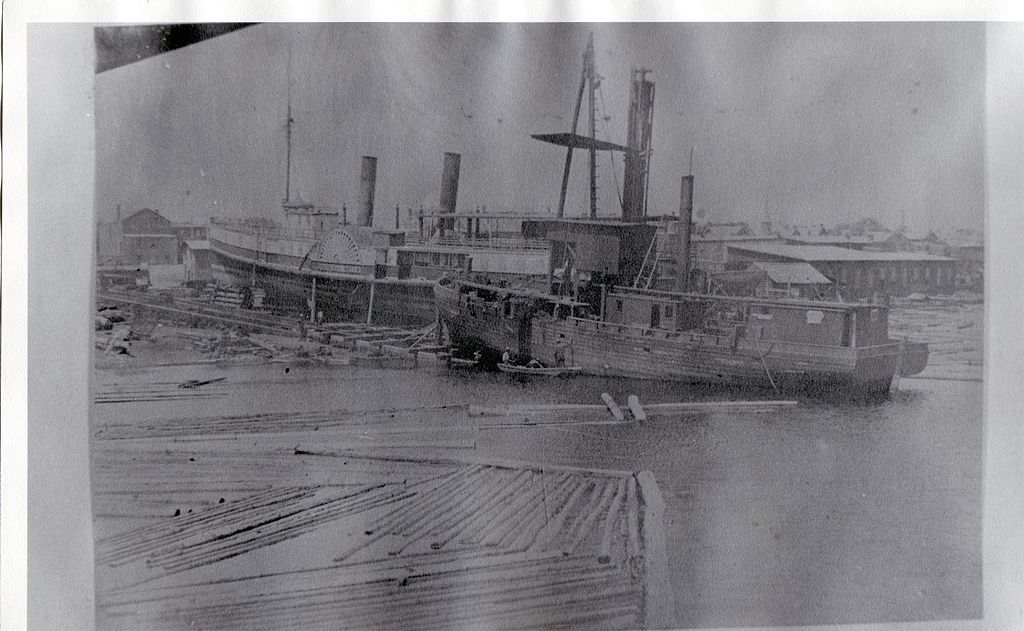

Shipyard. Note: not on Bayou St. John.

In the 1920s and ‘30s, thanks in no small part to the New Deal, Bayou St. John got a huge makeover.

No more mudflats and sunken garbage! No more crumbling levees! No more broken shell roads! No more houseboats and boathouses and ramshackle wharves! All of those things, after all, do not befit the name “Bayou St. John Aquatic Park,” which is what the weed-choked small craft parking lot, crisscrossed with outdated bridges, would become over the course of a few short years.

This is not to suggest the “old bayou” didn’t go down without a fight.

Perhaps the most heated argument to come out of this transformation occurred between Walter Parker, President of the Bayou St. John Improvement Association, and Joseph Dupuy, owner of the last remaining shipyard between Esplanade and Hagan Avenues. You see, the bayou’s makeover wasn’t only cosmetic; its essential character and function needed an overhaul as well. Its very role within the city, according to those at the helm (no pun intended!), needed redefining. After all—the Carondelet Canal, which once extended the bayou to the French Quarter along the path of today’s Lafitte Greenway, was no longer in use, and by 1938 was completely filled in. Without its manmade limb, the bayou served very little commercial purpose. And yet, old habits die hard. Along with the vestiges of other miscellaneous industries once connected with the waterway, two large shipyards remained active along the bayou’s lower banks by the time its makeover was proposed.

What’s wrong with a couple shipyards, you ask?

In short, they require the wrong kind of bridges.

In order for bigger boats to travel to the shipyards for repair, they needed the bayou’s drawbridges to open—most notably, the old Esplanade Bridge and the present-day Magnolia (or Cabrini) bridge. But Parker and the rest of the BSJIA did not envision drawbridges in the new Aquatic Park: they interfered with City Park-bound traffic, and, as is illustrated below, required much planning and many resources to operate.

According to Parker, opening the bridges required the services of a “specially trained crew” of at least five men (members of the Public Service Organization, and therefore not available to the city at a moment’s notice), often took upwards of 30-45 minutes to complete, and required notifications of the police department (for assistance detouring traffic), the Public Service Transportation Department (to reroute buses), Charity Hospital ambulances, and the fire department. Traffic had to be detoured to the Magnolia Bridge, and then, half an hour later, rerouted again so that the Magnolia Bridge could be opened. All, as Parker added for emphasis, so that “one boat can go to one boatyard for repair.” [1]

By the early 1930s, the Mullens Shipyard (near Esplanade Avenue) had agreed to be moved, but up until 1936, much to Parker’s chagrin, Dupuy refused to be relocated. But how would they finish their revetment work? And how would they install the proposed “fixed-span” bridges, with enough clearance only for canoes and other such small “pleasure craft”?

It wasn’t until Congress declared the bayou a “non-navigable stream” in 1936 that the city finally claimed the right to put its foot down. Eventually, the Dupuy shipyard was forced to move lake-ward. The bayou, goshdarnit, was to be recreational! I have to admit to having a soft spot for this shipyard, or at least the memory of it. Every time I pass by Dumaine Street’s intersection with the bayou, I imagine its skeletal hulls-in-progress, its busy workers, its stubborn desire to stay put.

1. City Engineer’s Bridge Records, 1918-1967, City Archives, Louisiana Division, New Orleans Public Library.